Why the US invested 94 times more in AI than India last year, why 62% of India's top engineering talent emigrates, why every semiconductor fab proposal keeps collapsing, and what this means for an IT sector already shedding tens of thousands of jobs to the very technology India cannot build.

In December 2025, India's IT Minister proudly tweeted that India had jumped to third place on Stanford University's Global AI Vibrancy Index, leapfrogging the United Kingdom, South Korea, Singapore, and Japan in a single year. The achievement was immediately assimilated into the familiar mythology of Indian exceptionalism: evidence that a rising tech superpower was closing the gap with the US and China. Karnataka's IT Minister declared the state "India's AI lighthouse." Government press releases followed in a cascade.

Nobody mentioned the scores. The United States scored 78.6 on the index. China scored second. India's score was 21.59. That is not a gap. It is a chasm, a 3.6x difference between first and third, dressed up in a ranking that flatters India's position because competition among countries outside the US-China duopoly is genuinely tight. Small score differences separate the remaining top 20. India beat South Korea (17.24) and the UK (16.64) convincingly, but the distance to the actual leaders reveals something the rankings alone cannot: India is not in the same race.

Development economists have a framework for this. When a country's position in a global value chain is defined by supplying low-cost labour and raw inputs while importing finished high-value products, the country is locked in a dependency relationship regardless of what headline growth numbers suggest. India's relationship to the global AI economy is precisely this: it supplies engineers, data, and back-office services, and imports the models, chips, and cloud infrastructure on which its own digital economy runs. The AI revolution is deepening this dependency, not alleviating it, and understanding why requires examining the structural failures that connect India's engineering education crisis, its brain drain dynamics, its semiconductor manufacturing collapses, and its chronic R&D underinvestment into a single, self-reinforcing system of technological subordination.

The Investment Chasm

The AI competition between the United States, China, and the European Union is a contest of trillions. American private AI investment reached $109.1 billion in 2024, more than all other countries combined. China invested $9.3 billion. The EU has approximately $8 billion. India's contribution was $1.16 billion, roughly 1% of the global total from a country with 18% of the world's population.

These numbers require a development economics lens for accurate interpretation. Investment is a flow. What matters for AI capability is the accumulated stock: compute infrastructure, trained researchers, institutional knowledge, and manufacturing capacity. India's flows have been negligible for so long that its stocks are depleted across every dimension. The United States controls approximately 75% of global GPU cluster capacity. India's entire IndiaAI Mission has procured 38,000 GPUs, fewer than a single hyperscaler facility in the United States operates. India's best supercomputer (AIRAWAT, 13.17 petaflops) is 130 times less powerful than America's El Capitan (1.74 exaflops). On research output, India ranks 4th globally in AI publication volume but only 15th in citation impact, the classic quantity-over-quality problem that development economists recognise in every sector India scales: volume without value addition.

The comparison with China is instructive and reveals how divergent policy choices compound over time. In 2000, China's R&D spending was comparable to India's as a share of GDP. China now invests 2.65% of GDP in research; India invests 0.64%. China holds nearly 70% of global AI patents. China's AI private investment, at $9.3 billion, is eight times India's. The divergence was a policy choice sustained over two decades: China chose to build indigenous technological capacity through massive state investment, forced technology transfer, strategic industrial policy, and a $47.5 billion semiconductor fund in 2024 alone. India chose to supply labour to the global services economy and let the market sort it out.

The market sorted it out exactly as dependency theorists would predict. Value creation concentrated in the countries that invested in productive capacity. India captured the labour-cost arbitrage gains: real but modest, widely distributed but shallow, and vulnerable to the next technological shift. China captured the value chain: manufacturing, IP, platforms, and increasingly the foundational models themselves (DeepSeek's open-source LLMs demonstrated in early 2025 that Chinese labs can compete at the frontier). Both countries started from roughly similar positions of technological backwardness in the early 1990s. The fact that one now competes with the United States for AI supremacy while the other struggles to retain its own engineering graduates tells you everything about the relationship between state investment and technological capability.

The Engineering Factory: Credential Inflation as Development Failure

India has 5,875 AICTE-approved engineering institutions that produce approximately 1.5 million graduates annually. No country on earth except China matches this volume. The number ought to be a source of competitive advantage. Instead, it represents one of the largest misallocations of human capital in modern economic history, and it illustrates a development economics concept that India embodies more visibly than perhaps any other country: credential inflation without human capital formation.

Human capital theory, as formulated by Gary Becker and Theodore Shultz, argues that education investments generate economic returns through increased worker productivity. India's engineering education system inverts this logic. AICTE's own chairman acknowledged in September 2025 that "only about half of India's engineering graduates are considered employable in the modern industry." The India Skills Report 2025, prepared by CII with AICTE, puts engineering employability at 71.5%, but this aggregate conceals vast internal disparities that make the number nearly meaningless. NASSCOM has historically reported that just 25% of Indian engineering graduates can work in IT services, the least demanding segment of the tech economy. A study published in PNAS found US computer science seniors outperforming their Indian counterparts by 0.76 to 0.88 standard deviations.

The structure explains the outcome. India's 23 IITs admit roughly 17,000 to 18,000 students annually: 1.4% of total engineering enrollment. More than 90% of engineering graduates come from private, non-autonomous, state-level institutions that vary widely in quality. Many were established during the 2000s boom, when state governments approved engineering colleges without regard for faculty availability, laboratory infrastructure, or employment outcomes. The result was predictable: 3 to 6 lakh vacant seats annually and an entire generation holding degrees that serve as expensive signalling devices rather than evidence of capability. For AI specifically, only 46% of graduates are employable in AI/ML roles, meaning the majority of graduates from a country positioning itself as a global AI player cannot perform basic AI-related work.

The faculty crisis makes reform nearly impossible. AICTE mandates a 1:20 faculty-student ratio, yet shortages persist across the system. At the newer IITs established in 2008-09, a CAG audit found infrastructure delays, faculty shortages, and enrollment below targets at all eight institutions. If even IITs cannot recruit adequately, the situation at thousands of lower-tier colleges is catastrophic. The reason is economic: teaching careers cannot compete when a fresh IIT graduate's starting package in industry exceeds what most college professors earn after a decade. This is not a market failure. It is the market working perfectly, revealing how little the Indian state values the production of knowledge.

What development economists should recognise here is a structural analogue to agricultural extension failures in low-income countries: a system that produces volume (graduates, such as crop yields) while degrading the underlying capacity (faculty quality, such as soil fertility) required to sustain quality over time. India is mining its education system for short-term output and calling the depleted result "demographic dividend."

Brain Drain as Path Dependency

If the mass engineering pipeline produces quantity without quality, India's elite pipeline produces quality and exports it. This is not an accident. It is a predictable consequence of systematic underinvestment in domestic research infrastructure and operates through the self-reinforcing dynamics that development economists call path dependence: the best leave because institutions are weak; institutions weaken further because the best have left, making the next cohort even more likely to leave.

A 2023 NBER study by Choudhury, Ganguli, and Gaule tracked the top 1,000 scorers on the 2010 IIT Joint Entrance Exam. Among these students, the very best engineering talent India produces, 36% had emigrated. Among the top 100, 62% had left. Among the top 10, nine out of ten were working abroad. The primary reason was higher education: 83% moved to pursue a Master's or PhD, drawn by access to cutting-edge research, world-class collaborators, and computing infrastructure that Indian institutions simply do not offer.

India's talent flow index, as measured by the Georgetown CSET, stands at -0.32 (negative indicating net outflow), compared with 6.29 for the United States. The OECD reports that India is the single largest source of highly educated migrants globally, with 3.12 million in OECD countries alone. The diaspora's achievements make the loss concrete. Ashish Vaswani, a BIT Mesra graduate, co-authored "Attention Is All You Need" while at Google Brain, the 2017 Transformer paper underlying every major large language model. Roughly 65% of leading US AI companies have Indian-origin leadership connections. Indian engineers contribute an estimated $198 billion annually to the US economy.

The compensation gap explains the individual rational choice: a mid-level AI engineer earns approximately $250,000 in the US versus $40,000 to $50,000 in India. But from a development economics perspective, salary is a symptom, not a cause. The deeper issue is that India lacks the ecosystem, the density of world-class research peers, the computing resources, the venture capital willing to fund frontier work, and the institutional autonomy for researchers that would make staying a viable choice for someone whose comparative advantage is in pushing the boundaries of what AI can do. The brain drain is not a failure of patriotism. It is a failure of state capacity.

There is a counter-narrative that Trump-era H-1B restrictions have reportedly led 30-40% of students to reconsider returning. American tech firms added 32,000 jobs in India during 2025. But examine what these jobs are: they are overwhelmingly in application development, IT services, and the 1,800+ Global Capability Centres employing 1.9 million people. These are implementation and support roles, not frontier research.

The talent that matters most for AI leadership, the people building foundational models and designing next-generation architectures, continues to work in Silicon Valley, Seattle, and London. India gets the call-centre version of the AI economy, which is exactly what dependency theory would predict.

India also produces approximately 24,000 to 29,000 PhDs annually across all fields, compared to roughly 58,000 research doctorates in the US (NSF Survey of Earned Doctorates, 2023) and over 50,000 STEM PhDs in China. Georgetown CSET projects will reach 77,000 by the end of this decade. Universities account for only 9% of national R&D spending, compared to 39% in Canada and 36% in Australia.

India has 262 researchers per million population; South Korea has 9,435; Israel has 8,342. Without competitive compensation, state-of-the-art labs, or meaningful research budgets, no rhetoric about becoming an AI superpower will convince a talented 22-year-old to stay for a PhD when Stanford is offering full funding, a stipend three times higher, and access to GPU clusters that exceed India's entire national allocation.

Thirty Years of Semiconductor Failure: When Institutions Cannot Execute

India's semiconductor ambitions provide the clearest case study of what development economists call institutional failure: not the absence of policy intentions, but the absence of state capacity to implement them. The facts are simple. As of early 2026, India has zero chip fabrication capacity. All semiconductors used in the country are imported.

The India Semiconductor Mission was launched in December 2021 with a budget of Rs 76,000 crore ($10 billion). Much of the public discourse around it has been actively misleading. Micron's $2.75 billion Gujarat facility, frequently described as a semiconductor plant, is an Assembly, Test, Marking, and Packaging (ATMP) facility that processes imported wafers into finished products. It does not fabricate a single chip. This distinction is consistently elided in government communications and media coverage.

The only approved fabrication project is Tata Electronics' partnership with Taiwan's PSMC, an $11 billion facility in Dholera, Gujarat, targeting production in late 2026 or 2027. It will manufacture chips at 28nm to 110nm, corresponding to mature technology nodes two to three generations behind the current state of the art. TSMC is producing at 3nm and moving to 2nm. India is building capacity for automotive and power management chips, not AI accelerators.

Three major fab proposals collapsed in sequence. The $19.5 billion Vedanta-Foxconn venture fell apart in July 2023 when Foxconn withdrew, citing the inability to secure a technology partner. Tower Semiconductor's partnership with Adani, approved by the Maharashtra government in September 2024, was quietly abandoned by Tower in late 2024 and formally shelved by Adani in May 2025 after concluding that the venture lacked commercial viability. Adani's internal assessment reportedly found that "the market is still nascent," questioning whether chips manufactured in India could find domestic buyers. Zoho also suspended its $400 million compound semiconductor project the same month. This was Tower Semiconductor's third failed attempt at a fab in India, following collapses in 2012 and 2017.

The historical pattern matters because it reveals a structural problem, not a series of unfortunate coincidences. In the late 1980s, India's Semiconductor Complex Ltd (SCL) in Chandigarh operated at 0.8-micron processes, just one generation behind Intel and Toshiba. A fire destroyed the facility in 1989; liberalisation in 1991 enabled cheap imports that eliminated incentives for reconstruction. In the 1960s, Fairchild Semiconductor chose Malaysia over India due to bureaucratic delays. In 2005, a multinational relocated its project to China due to import duties.

In 2013-14, two consortia granted Letters of Intent, but both withdrew. The recurring causes are identical across decades: bureaucratic delays, infrastructure gaps (ultrapure water, reliable power, waste processing), inter-ministry coordination failures, inability to deliver committed subsidies on time, and the absence of the kind of sustained, technocratic state capacity that Taiwan, South Korea, and now even Vietnam have demonstrated.

India has genuine strength in chip design, with approximately 20% of global semiconductor design engineers, including AMD's largest design centre in Bengaluru. But design without fabrication is the semiconductor equivalent of India's broader economic position: drawing blueprints for products other countries manufacture and sell back at a premium. It is precisely the kind of partial integration into global value chains that produces income without building capability.

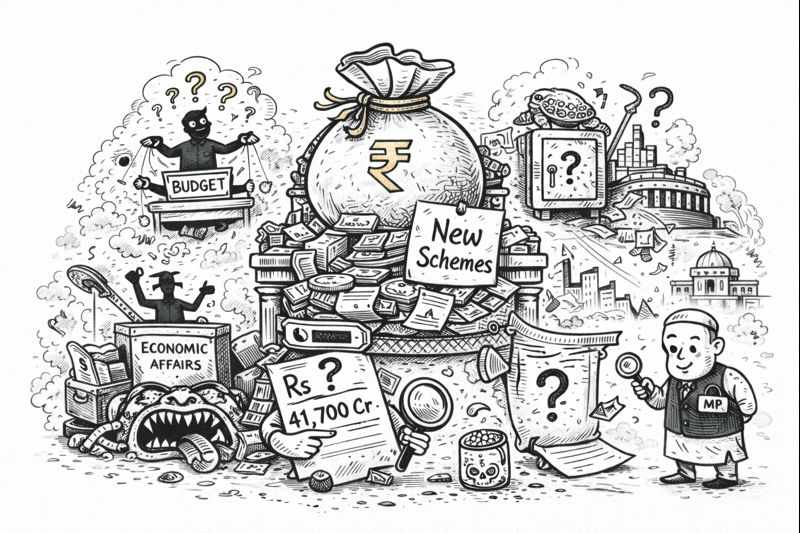

The IndiaAI Mission: Competent Response, Wrong Order of Magnitude

India's official AI policy response demonstrates a genuine effort at a scale that would be respectable from a country not claiming to be an AI superpower. The IndiaAI Mission, approved in March 2024 with a Rs 10,372 crore ($1.25 billion) five-year budget, has exceeded some targets. GPU deployment reached 38,000, exceeding the original goal of 10,000. The IndiaAI Compute Portal offers subsidised access at less than $ 1 per hour. Twelve startups have been selected to build sovereign AI models, including Sarvam AI, developing a 120-billion-parameter LLM and BharatGen, building a multimodal model supporting 22 Indian languages. The AIKosh dataset platform hosts 5,500+ datasets across 20 sectors.

These are NOT nothing. For a country at India's income level, the programme is competent. The problem is that competent is not the same as adequate, and the gap between the two is measured in orders of magnitude.

India's entire five-year AI budget equals approximately 1% of US private AI investment in a single year. Those 38,000 GPUs are a meaningful national resource, but American hyperscalers operate clusters of 100,000+ GPUs each. When OpenAI or Anthropic trains a frontier model, the compute involved exceeds India's entire national allocation.

The announcement-implementation gap, a chronic Indian governance problem, persists alongside genuine achievements: the 2018 NITI Aayog National Strategy for AI was a discussion paper with no dedicated budget. Promised Centres of Excellence materialised slowly, if at all. MeitY oscillated between requiring government approval for AI model deployment (March 2024) and retracting it amid industry backlash, creating regulatory uncertainty that discourages precisely the long-term investment India needs.

The IT Services Reckoning: When Cost Arbitrage Meets Automation

The development economics implications of India's AI deficit are not abstract projections. They are arriving now, in the form of structural disruption to the sector that built India's urban middle class, and they illuminate a fundamental vulnerability in India's growth model that AI is exposing with brutal clarity.

India's economic rise since 1991 has been unusual among developing countries: it largely skipped manufacturing and built growth on services exports, particularly IT outsourcing. This was celebrated as a new model of development, proof that countries could leap from agriculture to services without the intermediate industrial stage that classical structural transformation theory (Lewis, Chenery, Kuznets) treated as essential. Development economists were always sceptical, noting that services-led growth produced a narrow urban middle class while leaving the bulk of the workforce in low-productivity agriculture and informal employment.

Manufacturing absorbs large numbers of semi-skilled workers and generates technology spillovers across the economy; IT services absorbs a small elite and generates consumption spillovers in a few cities. India's manufacturing share of GDP actually declined from 17% to 13% between 2010 and 2023, even as the "Make in India" slogan proliferated.

The AI revolution is vindicating that scepticism with a vengeance. India's "comparative advantage" in IT services was never really about innovation or proprietary technology. It was cost arbitrage: Indian engineers performed the same tasks as American engineers for a fifth of the price. AI eliminates cost arbitrage by performing those tasks at near-zero cost. The country built a $283 billion industry on a foundation of cheap cognitive labour that is being automated by precisely the technology it failed to develop.

India's IT industry generated $283 billion in revenue in FY2025, employed 5.80 million people directly, and contributed over 7% of GDP. TCS announced 12,261 layoffs in July 2025, 2% of its workforce, the largest in the company's history. Infosys eliminated 26,000 positions in FY2024; Wipro shed 24,500; Tech Mahindra cut 10,700. In total, 80,000 jobs have been cut over 18 months. Hiring collapsed: the six largest firms added only 3,800 employees in a recent quarter, a 72% decline. Industry forecasts suggest up to 500,000 jobs could disappear within two to three years.

As Phil Fersht of HfS Research observed, the impact of AI is eroding the people-intensive services model. Clients now demand 20-30% price reductions by leveraging automation. TCS introduced a bench policy: engineers not assigned within 35 days must be retrained or exit the program. The comfortable middle-class employment that IT services offered, the backbone of consumption-driven urban growth in Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Pune, and Chennai, is structurally shrinking.

The bigger structural risk is the dependency relationship this creates. Approximately 90% of India's AI workloads run on overseas cloud servers. Chips come from Taiwan and South Korea. Foundational models come from American companies. India generates roughly 20% of the world's data but holds just 3% of global storage capacity. This is the digital equivalent of the colonial resource-extraction model that development economists have studied for decades: India supplies raw inputs (data, labour) and imports the processed products (AI models, cloud services, chips) at a premium. The value capture happens elsewhere.

The dependency intensifies as AI becomes more central to economic activity, not less.

0.65% of GDP, Unchanged for a Decade

Every structural failure described above can be traced to a single number: India's Gross Expenditure on R&D (GERD) is 0.64-0.67% of GDP, essentially unchanged for over a decade. South Korea invests 5.2% of its GDP. Israel invests 6.3%. The US invests 3.5%. China invests 2.65% and rising. The global average has reached approximately 2%. India, at 0.64%, is below Brazil (1.3%), below Russia (1.1%), and below the level at which any country has successfully built a technology-intensive economy.

The composition is as distorted as the level. In developed economies, private industry funds 70%+ of R&D. In India, the structure is inverted: the central government provides 43.7%, private industry only 36.4%. Government R&D concentrates in defence (DRDO, 30.7%) and space (ISRO, 18.4%), with limited allocation to industrial or AI research. Universities receive just 9% of R&D funding. Education is constitutionally a "concurrent subject" split between the centre and the state; state governments contribute only 6.7% of GERD. The National Education Policy 2020 recommends 6% of GDP for education spending. This target was originally set in 1968. It has never been achieved in over fifty years.

For development economists, this is the heart of the matter. R&D spending is the flow that builds capability stock. Compound interest works against underinvestment: a 0.64% annual rate instead of 2.5% is not a linear shortfall but an exponential one, because research capacity builds on itself. A PhD student trained in a well-funded lab with modern equipment produces research that attracts more funding, which trains more students, which produces more research. A PhD student trained in an underfunded department with 1990s-era equipment produces a thesis and then leaves for a country where the cycle runs in the right direction.

India's R&D flow has been so low for so long that its accumulated stock, research infrastructure, trained researchers, institutional knowledge, and laboratory equipment are depleted to a degree that any short-term budget increase cannot repair. China's divergence from India was not the result of a single policy decision but of two decades of sustained, compounding investment. Reversing India's position would require the same sustained commitment over a similar timeframe, beginning immediately, with no guarantee of political will to maintain it across electoral cycles.

The private sector's low R&D contribution is not a mystery either. India's IT services giants, TCS, Infosys, Wipro, and HCL, are fundamentally labour arbitrage businesses, not technology companies. Their business model involves performing work specified by foreign clients using Indian engineers paid a fraction of Western salaries. This model generates revenue without generating intellectual property. TCS's R&D spending as a percentage of revenue is a fraction of that of companies such as Google, Microsoft, or even Samsung. The Indian private sector does not invest in R&D because the dominant industry does not need to; it competes on cost rather than on innovation. This is the structural consequence of services-led growth without manufacturing, and AI is now eating the cost advantage that made the model work.

The Demographic Dividend Inverted

India's development model has centred on the demographic dividend: 900+ million working-age people are expected by 2030, and 7-8 million youth are joining the labour force annually. The AI revolution is inverting this narrative from asset to liability.

The 2024 India Employment Report (ILO) found that 82.9% of all unemployed Indians are youth aged 15-29. The education paradox deepens: 65.7% of the unemployed are educated youth, up from 54.2% in 2000. The unemployment rate among graduates (29.1%) is nine times that of illiterate workers (3.4%). More schooling correlates with a higher probability of unemployment because the institutions that teach and the economy that demands have diverged so completely that a degree has become a signal of aspiration rather than of capability.

Approximately 28.5% of Indian youth are NEET (Not in Employment, Education, or Training), rising to 48.2% for young women. Only 4% have access to vocational training. GDP growth has declined from 7.8% (2003-2015) to 5.8% (2014-2024), below the 8% threshold needed to absorb new labour force entrants.

Now add AI to this equation. The IT sector, which has absorbed millions of engineering graduates, is contracting. Routine cognitive work is being automated across industries. The entry-level white-collar jobs that converted engineering degrees into middle-class incomes are disappearing. India has millions of young people entering the workforce each year, into an economy that simultaneously fails to create jobs and eliminates existing ones through automation.

The middle-income trap, as defined in the development economics literature, occurs when a country exhausts the gains from cheap labour without developing the innovation capacity to compete at higher value levels. India's version of this trap has a uniquely cruel twist: it may hit before the country has even reached middle-income status for the majority of its population. Per capita income remains below $3,000.

The gains from IT services were concentrated in a handful of urban centres while 45% of the workforce remains in agriculture. If the services sector contracts before manufacturing expands (and India's manufacturing share of GDP continues to decline), the country faces a structural dead end: too expensive for mass low-skill manufacturing relative to Bangladesh and Vietnam, too capability-poor for high-skill innovation relative to China and the West, and now losing the services niche that was supposed to be the bridge between the two. The demographic dividend window is projected to close by 2040-2051. If current trends hold, India faces aging before accumulating wealth, with neither the manufacturing base of an East Asian tiger economy nor the innovation capacity of a Western one.

What Would Transformation Actually Require?

Three pathways remain technically viable, though none is being pursued at an adequate scale, and all require a quality of institutional commitment that Indian governance has not demonstrated in the technology domain.

The first and most realistic is application-layer leapfrogging: using India's data scale, linguistic diversity, and digital public infrastructure to lead in AI deployment rather than AI creation. UPI's success demonstrates this is possible. Launched in 2016, UPI now processes 50% of the world's digital transactions, 20 billion transactions monthly, exceeding Visa's global daily volume. The success factors, government-private collaboration through NPCI, mandated interoperability, open architecture, and zero consumer fees, show India can execute technology transformations when institutional conditions align. Applying this model to AI for agriculture, healthcare, and governance could generate enormous development value without competing with frontier models. However, it entails permanent dependence on foreign infrastructure and foundational technologies.

The second is selective strategic autonomy: investing in sovereign compute capacity and indigenous models for sensitive applications (defence, governance, critical infrastructure). The IndiaAI Mission moves in this direction, but at a fraction of the necessary scale. Twelve startups building Indian-language models are a start. Rs 10,000 crore over five years is not.

The third is structural transformation: increasing R&D spending to 2-3% of GDP; reforming engineering education to prioritise quality over quantity (fewer colleges, dramatically better funded); creating globally competitive compensation and research infrastructure to retain elite talent; and building patient capital for deep tech over 10-20-year horizons. This is the only pathway that changes India's position in the global AI value chain rather than optimising within its current subordinate position. It requires the political will of a kind that no Indian government has demonstrated in science and technology. It requires closing underperforming engineering colleges rather than opening new ones. It requires paying professors more than IT managers. It requires accepting that semiconductor fabs will lose money for a decade before becoming viable. It requires, in short, the kind of patient, technocratic state capacity that built Taiwan's TSMC, South Korea's Samsung, and China's entire semiconductor ecosystem, none of which happened through market forces alone.

The arithmetic is unforgiving. India is competing with nations that invest 50-100x more in AI, spend 3-5x more on R&D as a share of GDP, and retain rather than export their elite talent. Semiconductor fabrication remains years from even mature-node production. The demographic dividend window will close within 15-20 years.

Development economics has a concept for what happens when a country produces exceptional individual talent but systematically fails to build the institutions, infrastructure, and incentives to deploy that talent at home. It is called a development failure. India exports engineers to develop AI in America and imports finished products to sustain its domestic economy. It provides data to train models owned by foreign corporations and compensates for access to the intelligence derived from its own information. It celebrates a Stanford ranking that places it third, while the gap between third and first grows wider every quarter.

Until this is recognised as a development failure rather than a "technology gap" requiring incremental policy adjustments, it will not be addressed as such. The IndiaAI Mission's Rs 10,000 crore is a bureaucratic response to a structural crisis. India does not need another mission. It needs a transformation, and it needed it a decade ago.

Further Reading

AI investment and global competition: Stanford HAI 2025 AI Index Report: Economy | Georgetown CSET: AI Ecosystem, Where Does India Stand | MIT Technology Review: Inside India's Scramble for AI Independence

Engineering education and employability: AICTE: BTech Admissions Surge | India Skills Report 2025 via IBEF | AICTE Project PRACTICE for Rural Colleges

Brain drain and talent: Choudhury, Ganguli and Gaule (2023), Top Talent, Elite Colleges, and Migration (NBER Working Paper 31308) | The Geostrata: India's Lost Talent | CIO: Restrictive H-1B Policies Drive Tech Talent Back

Semiconductor manufacturing: Tower Semiconductor Dropped India Fab (EE News) | Vedanta-Foxconn Collapse (Business Standard) | Tata-PSMC Fab Agreement | India's Fab Vision 2025: Lessons from Zoho and Adani (Electronics For You)

IT sector disruption: Reuters via The Star: TCS Layoffs Herald AI Shakeup of $283B Sector | CNBC: Why India's IT Sector Is Shedding Jobs | India's IT Outsourcing Falters as AI Triggers Mass Layoffs | SME Futures: Inside TCS's 12,000 Layoffs

R&D spending and research: DST: R&D Statistics at a Glance 2022-23 | PIB: Parliament Question on R&D Investment | WIPO: Global R&D Spending 2024 | Nature: India's Tech Innovation Engines Must Raise Their Game | Lowy Asia Power Index: R&D Spending

Employment and demographic dividend: ILO India Employment Report 2024 | IDEAs: The Crisis of Youth Unemployment | International Banker: Unemployed Youth Are India's Achilles Heel | The Wire: India Out of Work

Varna is a development economist and writes at policygrounds.press.

Write a comment ...