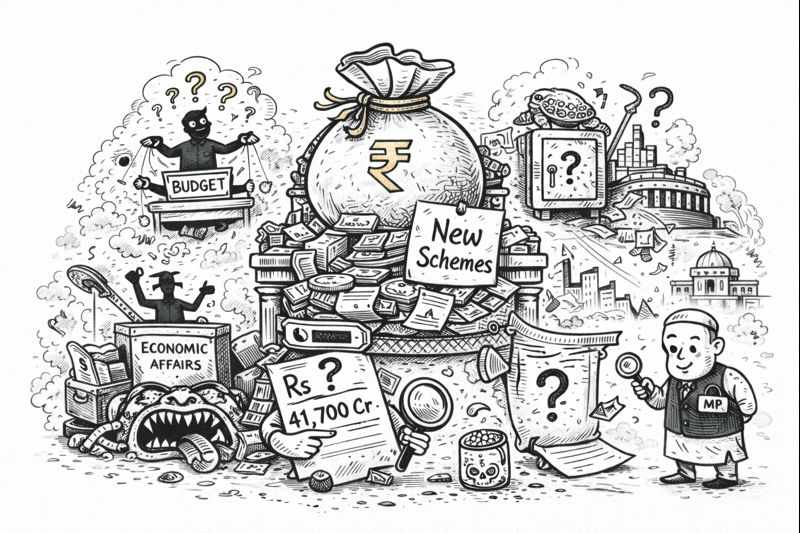

Inside the Demands for Grants, the off-budget funds, and the Rs 95,125 crore that Parliament did not vote on.

I have watched every budget speech since 2017. Most years, I follow a routine: television on, Demands for Grants (DFG) pulled up on a second screen, pen in hand for the annotation layer. The speech is usually political, and the numbers are usually the story. I know this. Budget day is the one day a year when the entire policy apparatus of the Indian state is, at least notionally, on display. The speech is a political document, but the documents tabled alongside it are the real thing: DFGs that show who gets what, OOMF entries that (sometimes) say what it is supposed to achieve, and expenditure profiles that reveal what was actually spent versus what was promised.

And yet, sitting in my living room on this Sunday morning, watching Nirmala Sitharaman deliver her ninth consecutive budget, I found myself genuinely stunned. Not by what was announced. By how badly it was done.

This was a budget presented against the backdrop of a global trade war triggered by Trump's tariffs, a rupee under persistent pressure, capital expenditure that peaked in 2023-24 and has flatlined since, youth unemployment that the government's own surveys acknowledge, and an informal workforce of roughly 48 crore people with no social security floor. The moment called for something. What we got was subheadings.

Shashi Tharoor, speaking to PTI afterwards, put it precisely: the speech was "completely short of an overall vision. What was it supposed to be about? Was it meant to proclaim a new era of reform? It didn't do that. Was it supposed to be performing some sort of belt-tightening? It didn't say that. What was it all about? It was a series of subheadings."

P. Chidambaram, who has served as Finance Minister four times and knows budget craft better than almost anyone alive in Indian politics, counted 24 new schemes, missions, funds, institutes, and committees, most of which he predicted would disappear quietly within a year. The budget, he said, failed "the test of economic strategy and economic statesmanship." Jairam Ramesh called it "totally lacklustre" and "non-transparent" because the speech gave no idea whatsoever of budgetary allocations for key programmes and schemes. Even Ashneer Grover, hardly an opposition figure, invoked his Shark Tank rebuke: "Bilkul time waste kiya aapne."

By the close of trading, Sensex had fallen 1,564 points, and Nifty had dropped 495 points. Around Rs 10 lakh crore in investor wealth was wiped out in a single session. The market's verdict was swift and unambiguous.

This essay is about what you find when you stop listening to the speech and start reading the budget documents themselves. I have spent the day going through the Demands for Grants, the Output-Outcome Monitoring Framework, the Expenditure Profile, the 16th Finance Commission report, and the government's own Implementation of Budget Announcements 2025-26. I built an interactive Budget Explorer that pulls together the data across sectors. What follows is what the numbers show. The picture is considerably worse than the speech suggests, and the mechanisms for obscuring it are more sophisticated than in any previous budget I have analysed.

The fiscal architecture of avoidance

The headline number is Rs 53.47 lakh crore in total expenditure, a 5.6% increase over last year's budget estimate. Below inflation, but not catastrophic on its face. The problem is not the top line. The problem is where the money actually sits.

This budget allocates at least Rs 95,125 crore to social spending through off-budget reserve funds that are outside normal parliamentary scrutiny. This is not a minor accounting detail. These are funds for employment (MGNREGA), health (NHM, PMJAY), national security technology, and agriculture infrastructure. The money is transferred into reserve accounts, often during the Revised Estimates, which receive minimal parliamentary debate, and then drawn down for spending without appearing as a "demand" that Parliament votes on line by line. The fund operations are disclosed in the notes to the relevant Demand for Grants, typically buried on page 115 onwards of a dense PDF.

Here is what that architecture looks like in practice. The National Employment Guarantee Fund (NEGF) routes Rs 30,000 crore for MGNREGA wages. The Pradhan Mantri Swasthya Suraksha Nidhi (PMSSN) routes Rs 30,725 crore in health cess proceeds for NHM and PMJAY. A brand new "Technology in National Security Fund" (TNSF) in DFG 30 (Economic Affairs) routes Rs 30,000 crore for something described in exactly one sentence: "Development of technology for the overall national security architecture." No OOMF entry. No committee scrutiny. No prior history. And the Agriculture Infrastructure Development Fund routes Rs 4,400 crore.

That adds up to Rs 95,125 crore. But there is more. An "Economic Stabilisation Fund" was allocated Rs 50,000 crore in the Revised Estimates 2025-26. The Expenditure Profile confirms this: it lists the transfer under "Other General Economic Services" as a provision "for meeting unanticipated expenditure arising in view of volatile global dynamics and uncertain global economic environment." It has not been drawn in BE 2026-27. There is no public explanation for what it is, no drawdown conditions, and no sunset clause. It is larger than the combined allocation for the Centrally Sponsored Schemes for school education. It simply sits there.

CSEP's working paper on off-budget borrowings provides the analytical framework for understanding why this matters: these mechanisms reduce parliamentary oversight, obscure the true cost of programmes, and make it nearly impossible for external analysts to track where money goes.

I wrote about the Rs 41,700 crore "New Schemes" mystery in DFG 30 in last year's budget. That line has now shrunk 95% to Rs 2,000 crore. The money did not vanish. It migrated into these reserve funds. The government has shifted from using one black box to using many smaller ones. What was a single line item that could be questioned in Parliament has become a distributed network of transfers that require a forensic accountant to trace. The direction of movement is unmistakable: away from transparency, not toward it.

Where jobs go to die: employment, formalisation, and the workers left behind

The budget rewrites the entire employment architecture in India, with a clear philosophy: formalisation is the goal, and everything else is expendable.

Start with MGNREGA. The programme provided a legally guaranteed 100 days of employment to any rural household that asked for it, funded entirely by the Centre. That is past tense now. MGNREGA has been replaced by VB-G RAM G, and the nature of that replacement tells you everything about this government's theory of social protection.

On paper, the combined allocation looks generous: Rs 95,692 crore for VB-G RAM G plus Rs 30,000 crore from the NEGF, a 43% increase that the government will cite in every press release. But MGNREGA was a Central Sector scheme, meaning the Centre paid 100% of wage costs. VB-G RAM G is a Centrally Sponsored Scheme with a 60:40 cost-sharing ratio. States now bear 40% of costs, including materials. The annual burden transferred to state balance sheets is approximately Rs 55,590 crore. Bihar alone faces Rs 2,576 crore in new obligations, about 0.23% of its GSDP. Tamil Nadu and Kerala have already opposed the shift.

The political economy here is not subtle. The Centre announces a 43% increase while quietly transferring Rs 55,590 crore in costs to state governments. States in fiscal distress, which is most of them, will face a choice between cutting other programmes or underfunding the employment guarantee. The net effect is a reduction in actual employment provision dressed up as an increase. This is not an accounting trick. It is a structural reassignment of fiscal responsibility from the level of government that collects most taxes to the level that has the least fiscal space. It is fiscal centralization presented as cooperative federalism.

And then there is the measurement problem. The OOMF entry for VB-G RAM G, the government's flagship Rs 95,692 crore rural employment replacement, says that both output and outcome targets are "not amenable" to quantification. Think about what that means. This is the government's own admission: it cannot or will not measure the impact of its largest new social programme. Jean Dreze has observed that raising the guarantee ceiling to 125 days is symbolic, given that 98% of registered households receive fewer than 100 days. The average in 2024-25 was 50 days. The ceiling is irrelevant when the floor is this far below it.

Meanwhile, the Ministry of Labour and Employment's allocation stands at Rs 32,666 crore, virtually unchanged from BE 25-26. But the Revised Estimate for 2025-26 was only Rs 12,688 crore. The ministry spent 39% of its budget. The gap is almost entirely explained by PM-VBRY's predecessor: the Employment Generation Scheme received Rs 20,000 crore in BE but spent just Rs 848 crore. A 4.2% spending rate. In 2026-27, the same scheme, renamed PM Viksit Bharat Rozgar Yojana (PM-VBRY), gets Rs 20,083 crore and targets 84 lakh first-time EPFO registrations and 1.44 crore re-joiners. Based on last year's spending pattern, the question is whether this money will actually be spent.

The budget's biggest casualties, though, are gig workers and the broader informal workforce. The story of what happened to them between Budget 2025-26 and Budget 2026-27 is a small masterclass in how Indian policy abandons its stated commitments.

Budget 2025-26 explicitly promised Ayushman Bharat health coverage for gig workers and mass registration on e-SHRAM. The government's own Implementation document confirms what happened: 12 aggregators were onboarded (Zomato, Swiggy, Uber, Ola, Amazon, Blinkit, Urban Company, Rapido, Zepto, Porter, Ecom Express, Uncle Delivery), three nationwide registration campaigns were conducted, and approximately 1 lakh workers registered out of a 1 crore target. That is 1% achievement.

Then in 2026-27, e-SHRAM's allocation was set to zero. The entire portal was merged into SRISTI for Rs 28 crore. For context, there are 31 crore registered unorganised workers on e-SHRAM. Rs 28 crore works out to 90 paise per worker per year. The Ayushman Bharat promise for gig workers? DFG 46 (Health) and DFG 64 (Labour) show no allocation line for it anywhere. It has been quietly shelved.

The total allocation for all schemes directly targeting informal and unorganised workers is Rs 482 crore. India has roughly 48 crore informal workers. That comes to Rs 10 per worker per year. By contrast, the EPS pension for formal sector retirees gets Rs 11,144 crore, and PM-VBRY for new formal sector entrants gets Rs 20,083 crore. The budget's employment architecture is built entirely around formalisation. If you are already informal, and most Indians are, the budget has almost nothing for you.

The Social Security Code Rules set a 90- to 120-day eligibility threshold. Zomato's own data shows its average delivery partner works 38 days per year. Most gig workers are excluded by design. This is the quiet core of the employment section of this budget: it builds an elaborate architecture for bringing workers into the formal system while spending almost nothing on the 48 crore people who cannot get in. The 43% headline increase in employment spending is real only if you count the money the Centre no longer pays, but states now owe.

The cess that eats its children: health accounting and its discontents

Total health allocation for the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare is Rs 1,05,530 crore, an 8.96% increase over RE 2025-26 that the government will rightly celebrate. NHM itself received Rs 39,390 crore, an increase of Rs 2,290 crore. But look at how the health budget is constructed.

Rs 30,725 crore flows through the off-budget PMSSN fund, financed by Health and Education Cess proceeds, not from fresh budget appropriation. The cess money enters the Union's accounts, flatters the total health figure, and simultaneously reduces the need for fresh allocation from the Consolidated Fund. Strip out the PMSSN component and the picture changes: the growth in direct budgetary support for health is considerably narrower than the headline 8.96% suggests.

The 4% Health and Education Cess was introduced in 2018 to finance "quality health services and universalised quality basic education." The Finance Bill 2026 retains this cess at 4%. Every salaried Indian pays it. But the money is routed into the PMSSN, which then disburses to NHM and PMJAY according to a schedule that is not voted on by Parliament in the normal way. The cess raises revenue that appears in the Union's accounts, flatters the total health allocation, and simultaneously reduces the need for fresh appropriation from the Consolidated Fund. Without access to the precise PMSSN fund flow data (disclosed only in the DFG notes, typically on page 115 onward), it is impossible for external analysts to determine how much of NHM's Rs 39,390 crore is fresh budget support and how much is a cess transfer. That opacity is the point.

There is a history here worth recounting. India's public health spending has been stuck at approximately 1.9% of GDP for years. The National Health Policy 2017 targeted 2.5% by 2025. We are in 2026. The gap has not narrowed in any meaningful way. The government collects a cess earmarked for health, routes it through an off-budget fund, counts it as health spending, and uses the inflated total to claim progress toward a target it has no intention of meeting. The NHM received Rs 39,390 crore, a genuine increase. But the question is what share of that comes from the cess fund versus fresh Consolidated Fund allocation. When Rs 30,725 crore in cess proceeds flows through PMSSN into the same DFG, the distinction between new money and repackaged cess receipts disappears inside the accounting. This is not accidental.

The 15th Finance Commission had provided health grants through local bodies worth Rs 70,051 crore over five years (roughly Rs 14,000 crore annually), which helped bridge exactly this kind of gap. It also provided school education grants of Rs 4,800 crore. The 16th Finance Commission has discontinued these sector-specific grants entirely. The Explanatory Memorandum confirms that the Commission recommended against sector-specific grants, and the government accepted that recommendation. So states lose the 15th FC health and education grants and pick up higher CSS cost shares from VB-G RAM G and other restructured schemes.

The DFG 42 (Transfers to States) data tells the story in precise numbers. Under the 15th FC, health grants of Rs 70,051 crore over five years were allocated to local bodies as a separate line. Under the 16th FC, grants to states are consolidated into local body grants (Rs 1,01,181 crore) and disaster management grants, with no earmarked health component. A new "Assistance to States for Public Health Infrastructure" line appears at Rs 4,200 crore, but it is funded through a "Health Security se National Security Cess Fund" that nets to zero in the demand. The states that relied on 15th FC health grants to supplement NHM funding now face a squeeze: they lose roughly Rs 14,000 crore in annual health grants while gaining untied local body grants with no health earmark.

The two speeds of Education spending

Combined education spending rose to Rs 1,39,289 crore, an 8.3% increase over BE 25-26. But this aggregates two very different stories.

Central Sector schemes, which are 100% centrally funded capital projects (university townships, AVGC labs, STEM hostels), surged 746% in school education and 60% in higher education. These generate headlines. They produce visible, photographable infrastructure. They carry the names of programmes that ministers can announce at press conferences.

Centrally Sponsored Schemes, which carry the bulk of operational school education funding, including Samagra Shiksha, PM-SHRI schools, and PM POSHAN (the mid-day meal programme), grew just 0.6%. That is a real-terms decline once you account for inflation.

The distinction between Central Sector and Centrally Sponsored Schemes is not an arcane budget classification. It determines who eats. Central Sector schemes build new buildings. Centrally Sponsored Schemes pay for the mid-day meals that keep children in school, the teacher training that determines whether those children learn anything, and the operational costs that keep existing schools functioning. A 0.6% increase in CSS funding while Central Sector funding surges is a budget that is investing in the photograph of education rather than the act of it.

The National Education Policy 2020 targeted 6% of GDP for education. Actual allocation sits at approximately 2.9%. The 15th Finance Commission's education grants, like its health grants, have been discontinued by the 16th FC. An "Education to Employment" High-Level Standing Committee was announced in the budget speech. It has no allocated budget line.

RE 2025-26 was 14% below BE for education, confirming the same chronic pattern visible across social sectors: generous budget estimates, quiet revised estimate cuts, and headlines driven by new capital announcements rather than the operational funding that keeps schools running. The government budgets for ambition and spends for austerity.

Champion MSMEs and the kirana store that does not exist in policy

The MSME announcements were among the few in this budget that contained actual structural ideas. The Rs 10,000 crore SME Growth Fund provides equity support for "Champion SMEs" based on select criteria. There is a Rs 2,000 crore top-up to the Self-Reliant India Fund. TReDS (Trade Receivables Discounting System) has been made mandatory for all CPSE purchases from MSMEs, and GeM has been linked with TReDS to share information with financiers. The development of TReDS receivables as asset-backed securities creates a secondary market for MSME invoices, which addresses a genuine credit constraint. A "Corporate Mitras" cadre, trained by ICAI/ICSI/ICMAI, will provide para-professional support in Tier-II and Tier-III towns. Two hundred legacy industrial clusters are slated for revival. The removal of the Rs 10 lakh per consignment cap on courier exports helps small exporters.

These are not trivial measures. Credit constraints and delayed payments are real barriers for MSMEs, and the TReDS reforms in particular target a well-documented structural problem.

But the framing matters. India has 7.47 crore MSME enterprises employing 32.82 crore people. They contribute 31% of GDP, 35% of manufacturing output, and 49% of exports, according to the Economic Survey 2025-26. The budget speech cited these numbers. The policies it announced will reach only a fraction of them.

The SME Growth Fund targets "Champion SMEs," which, by definition, are firms that have already reached a certain scale and meet select criteria for equity support. The vast majority of MSMEs are micro-enterprises, often single-proprietor operations with fewer than five workers, operating without formal accounts or access to platforms such as TReDS or GeM.

A kirana store owner in Muzaffarpur or a small welder in Coimbatore does not register on TReDS. Even if it disburses fully, the Rs 10,000 crore Growth Fund will reach perhaps a few thousand firms. The structural reforms around TReDS and GeM integration benefit firms already participating in government procurement. The 200 cluster revivals depend on state-level implementation in geographies where industrial policy capacity varies enormously.

This is a recurring pattern in Indian industrial policy: design programmes for the top of the pyramid while invoking the breadth of the base. The budget speech cited 7.47 crore enterprises. The credit access, equity support, and receivables financing measures it announced will probably reach a few lakh of them. The remainder operate in a policy vacuum where the only government touch-point is GST compliance, and even that drives many of them toward informality rather than away from it. When the budget allocates Rs 20,083 crore for EPFO-based formalisation and Rs 10,000 crore for equity to already-scaling SMEs, while spending Rs 28 crore on the portal that was supposed to register the country's informal workforce, the priorities are legible.

K.E. Raghunathan, National Chairman of the Association of Indian Entrepreneurs, made the point concisely: just as Production Linked Incentives are given to corporates, a "Value Added Incentive" should have been given to small and micro enterprises. The budget's MSME measures are real, but they are designed for the top tier of the sector, not the base.

What Rs 50 crore buys you: environment in the age of fiscal forgetting

The environment ministry's total allocation rose 10.1% to Rs 3,759 crore, but the growth is driven entirely by CAMPA (afforestation fund) disbursements. NCAP, the National Clean Air Programme, was cut from Rs 1,552 crore (BE 25-26) to Rs 1,091 crore, a 30% reduction. The Climate Action Plan receives Rs 50 crore.

Rs 50 crore. Roughly what the Central government spends on a single interchange flyover. For the entirety of India's national climate action planning.

Air pollution kills an estimated 1.6 million Indians annually, according to the Lancet. Only 23 of 130 NCAP cities have met even the revised, weakened PM10 reduction targets. CREA's 2025 progress report found that most cities lack even basic monitoring infrastructure. The Centre for Science and Environment's NCAP assessment documents that 64% of NCAP and 15th Finance Commission funds were spent on road dust mitigation (water sprinklers and sweeping), while industrial emissions received 0.61% of the outlay. CREA calls this "action without impact." RTI data for Delhi shows the capital spent just 17% of its NCAP air pollution funds over five years.

The programme has no PM2.5 source apportionment requirement, which means cities are spending money on road sprinklers when the problem may be industrial emissions, transport, or crop burning. There is no mechanism to direct funds toward the actual sources of pollution. And the budget speech did not mention air pollution at all. Not once. A country where 1.6 million people die from bad air every year, in a budget that found time to announce seaplane tourism and high-tech toy manufacturing, could not spare a sentence for the air its citizens breathe.

The well that ran dry: agriculture, water, and the collapse of execution

Agriculture allocation grew 2.6% to Rs 1,30,561 crore, below inflation. PM-KISAN, the direct income support programme that transfers Rs 6,000 per year to small and marginal farmers, has not been indexed since its 2019 launch. Adjusted for cumulative CPI inflation since then, that Rs 6,000 is worth approximately Rs 4,300 in 2019 prices. A roughly 30% real decline in the value of the transfer, affecting over 8 crore beneficiary households, and the budget made no correction.

The starkest execution failure in the entire budget belongs to Jal Jeevan Mission. JJM was allocated Rs 67,000 crore in BE 2025-26. The Revised Estimate is Rs 17,000 crore. That is a 75% gap between what was budgeted and what was spent, the largest shortfall among all Centrally Sponsored Schemes. Business Standard reports the reason: while the Finance Minister announced JJM's extension to 2028 in last year's budget, the Union Cabinet had not formally approved the extension, legally freezing the release of fresh tranches. The Expenditure Profile confirms this variation, listing "Water Supply and Sanitation" as one of the largest decreases between BE and RE 2025-26: a drop of Rs 50,000 crore.

The response in BE 2026-27? The government budgeted Rs 67,670 crore. Nearly identical to the number it failed to spend last year.

No accountability for the delivery failure. No explanation for why Rs 50,000 crore could not be absorbed. No structural reform to the implementation pipeline. Just the same number, resubmitted. When a government budgets Rs 67,000 crore, spends Rs 17,000 crore, and then budgets Rs 67,670 crore again without explanation, the Budget Estimate is not a spending plan. It is a press release.

The food subsidy provides an instructive contrast. At Rs 2,35,047 crore, it is the single largest social sector expenditure, larger than defence revenue spending. The Revised Estimate for food subsidy actually exceeded the Budget Estimate, reflecting real demand. The food distribution system works precisely because the National Food Security Act made it legally binding, because the Public Distribution System, for all its flaws, has decades of operational infrastructure, and because the political cost of visibly denying food is higher than the political cost of quietly underspending on employment guarantees or clean air programmes. The lesson is not complicated. Programmes backed by strong legal entitlements and operational infrastructure get spent. Discretionary allocations, however generous on paper, get cut at RE. If the government wanted its social programmes to work, it would make more of them legally binding and build the state capacity to deliver them. It has chosen not to.

Lakhpati Didi and the announcement that has no budget line

The Ministry of Women and Child Development's allocation grew 4.8% nominally to Rs 28,183 crore, roughly zero real growth at current inflation levels. RE 2025-26 was 9.4% below BE, confirming persistent underspending. New schemes were announced in the speech (SHE-Marts, Lakhpati Didi expansion) without corresponding budget increases. DFG 101 shows the CSS umbrella (which carries Mission Shakti, Mission Vatsalya, and Saksham Anganwadi) growing 4.7%, a real-terms standstill.

The Anganwadi system, India's largest early childhood care infrastructure, serves over 8 crore beneficiaries, primarily children under six and pregnant and lactating women. Its operational funding comes through the Saksham Anganwadi component. Anganwadi workers are paid honoraria, a practice that has been the subject of protests across states for years. The budget offers no revision. The Lakhpati Didi programme, which aims to create one crore women with annual SHG incomes over Rs 1 lakh, was announced as an expansion without specifying the additional budget it requires. This is the announcement-without-allocation pattern in miniature: a speech commitment with no DFG footprint.

Housing and Urban Affairs was cut 11.6% year on year. The CSS component (Smart Cities, SBM-Urban) dropped 17.6% from BE 25-26. Smart Cities Mission, which I worked on briefly, was always more about visible metrics than underlying infrastructure. I spent my time there making numbers look good on screens. The programme's budget trajectory confirms the pattern I saw from inside: generous initial allocations, declining real support, and a focus on countable outputs over liveable outcomes. The SASCI announcement of "Rs 2 lakh crore support to states for urban infrastructure" is not a direct allocation. It appears to be a loan or guarantee framework spread over multiple years, similar to previous announcements that generate large headline numbers without immediate budget commitment. The mechanism and drawdown conditions are not specified in the DFG.

The fiscal squeeze on states: what the 16th Finance Commission changes

The 16th Finance Commission report, tabled alongside this budget, deserves separate treatment because its recommendations compound every sectoral problem I have described.

The Commission retained the vertical share of tax devolution at 41%, the share of central tax revenues that flows to the states. The Explanatory Memorandum confirms that the government accepted this recommendation. On the face of it, continuity. But the 16th FC discontinued the health grants through local bodies (roughly Rs 14,000 crore annually under the 15th FC) and school education grants (Rs 4,800 crore over four years) that the 15th FC had provided. It recommended against earmarked grants, preferring untied local body grants (Rs 1,01,181 crore) and disaster management grants.

The logic of untied grants is that states know their priorities better than the Centre does. In principle, this is sound. In practice, it removes the only mechanism that ensured minimum health and education spending in states that would otherwise deprioritise these sectors. A state government facing fiscal pressure will use untied grants for the most politically visible expenditure, which is rarely primary healthcare or anganwadi operations.

Combine this with the MGNREGA-to-VB-G-RAM-G conversion (Rs 55,590 crore in new state obligations), the discontinuation of health grants through local bodies (roughly Rs 14,000 crore annually) and school education grants, and the rising CSS matching requirements, and you have a picture of systematic fiscal stress on state governments. The Centre collects the taxes, announces the schemes, takes the credit for the headline allocations, and transfers a growing share of the actual cost to states whose fiscal space is shrinking. Mallikarjun Kharge's complaint that "federalism has become a casualty" is a political statement, but the DFGs and the 16th FC recommendations give it a precise numerical content.

What the numbers tell, when you are willing to listen

P. Chidambaram said the government either had not read the Economic Survey or had chosen to ignore it. He pointed out that revenue receipts fell short, spending overshot estimates, and capital expenditure was cut. Centre's direct capex has stayed flat at around 3.1% of GDP in both 2025-26 (RE) and 2026-27 (BE), even as the FM announced Rs 12.2 lakh crore as the "highest ever" allocation. Rahul Gandhi called it a budget "blind to India's real crises: youth without jobs, falling manufacturing, investors pulling out capital, household savings plummeting, farmers in distress." Mallikarjun Kharge said, "Federalism has become a casualty... this Budget offers no solutions, NOT even slogans."

These are political statements, and they carry the weight of partisan interest. But the numbers, the actual DFGs and OOMF entries and reserve fund structures that I have been reading all day, support a more specific diagnosis.

The budget has three consistent features across every social sector I examined.

First, chronic underspending. The gap between Budget Estimates and Revised Estimates is not noise. It is a signal. JJM spent 25% of its allocation. The Labour Ministry spent 39%. The Employment Generation Scheme spent 4.2%. Education underspent by 14%. Women and Child Development underspent by 9.4%. When a government consistently fails to spend what it budgets and then re-budgets the same amounts without explanation, the Budget Estimate is not a spending plan. It is a press release.

Second, structural cost-shifting. The conversion of MGNREGA from a Central Sector to a Centrally Sponsored Scheme shifts Rs 55,590 crore in annual costs to states. The 16th Finance Commission's discontinuation of health grants through local bodies (~Rs 14,000 crore annually) and school education grants removes another layer of support. States simultaneously face rising CSS matching requirements and declining central support.

Third, the reserve fund architecture. Rs 95,125 crore in spending now flows outside the normal budget process. An additional Rs 50,000 crore sits in a fund with no public explanation. The "New Schemes" black box has been replaced by multiple, smaller black boxes. The direction of travel is toward less transparency, not more.

There is a fourth pattern worth naming, though it cuts across the first three: the systematic devaluation of legal entitlements. MGNREGA was a rights-based programme. Its replacement has no measurable performance standard. The Social Security Code promises gig worker coverage but sets eligibility thresholds that most gig workers cannot meet. PM-KISAN is not technically an entitlement, but it functions as one for 8 crore households, and its value has been allowed to erode by roughly 30% without adjustment. Even Jal Jeevan Mission, framed as a universal "Har Ghar Jal" promise, underspent by 75% and then re-budgeted the same number. When promises lose their teeth but keep their names, the budget becomes a document of aspiration management rather than fiscal planning.

I do not think this budget is uniquely terrible. I think it is a refinement of a pattern that has been developing for several years: the gap between announcement and execution, between Budget Estimate and Revised Estimate, between headline allocation and actual spending by the people who need it. What is new this year is the sophistication of the accounting mechanisms that make this gap harder to see. Reserve funds, off-budget cess routing, CSS cost-sharing conversions, untied grant consolidation. Each of these individually is defensible. Together, they constitute a system for making social spending look larger than it is, while transferring costs to governments that cannot afford them.

And the speech was so poor that, for once, even people who do not normally read DFGs noticed something was wrong.

I went back to my second screen this evening, the one with the Demands for Grants still open, and scrolled through the tabs I had annotated over the course of the day. Employment. Health. Education. Environment. Agriculture. Women and Child Development. Housing. In every sector, the same architecture: generous announcements, inadequate operational funding, chronic underspending from last year reproduced as this year's targets, and a growing web of reserve funds and cost-sharing arrangements designed to make the numbers harder to follow.

The food subsidy is the instructive exception. It works because the National Food Security Act made it legally binding, because the PDS has decades of operational infrastructure, and because the political cost of visibly denying food is higher than that of quietly underspending on employment guarantees or clean air. The lesson is not complicated. If the government wanted its social programmes to work, it would make more of them legally binding and build the state capacity to deliver them. It has chosen not to.

If you want to see the numbers for yourself, the Budget 2026-27 Explorer puts the full sector-by-sector data in one place with links to every primary source.

Further Reading

Primary Budget Documents

Budget Speech · All Demands for Grants · Statement 1 (Aggregate Expenditure) · Expenditure Profile · OOMF · Finance Bill · Memorandum Explaining Provisions · 16th Finance Commission Report · Implementation of Budget Announcements 2025-26

Key DFGs by Sector

DFG 30 (Economic Affairs / Reserve Funds) · DFG 87 (Rural Development / VB-G RAM G) · DFG 64 (Labour & Employment) · DFG 46 (Health) · DFG 25 (School Education) · DFG 26 (Higher Education) · DFG 28 (Environment) · DFG 1 (Agriculture) · DFG 42 (Transfers to States) · DFG 63 (Drinking Water / JJM) · DFG 101 (Women & Child Development)

External Research

CREA: Tracing the Hazy Air, 2025 NCAP Progress Report · CSE: NCAP Assessment · CSEP: Off-Budget Borrowings · The Wire: VB-G RAM G Analysis

Interactive

Budget 2026-27 Explorer (policygrounds.press): Full sector-by-sector data, source-linked tables, and the reserve fund architecture in one place.

Varna is a development economist and writes at policygrounds.press.

Write a comment ...