Regulations meant to prevent student suicides triggered Supreme Court intervention, BJP resignations, and exposed how India destroys thousands of crores in human capital annually through institutional discrimination while allocating minimal resources to equity enforcement.

On 17 January 2016, Rohith Vemula wrote a letter before hanging himself in his friend's hostel room at the University of Hyderabad. He was 26 years old, a PhD scholar studying the movement of stars and planets. Two weeks earlier, the university had suspended him along with four other Dalit students. They were barred from entering hostels, the mess, administrative buildings, and common areas. Their fellowship payments of Rs 25,000 per month were stopped. For weeks, they lived in a protest tent outside the campus shopping centre, calling it "Velivada" (Dalit Ghetto), with a photograph of Babasaheb Ambedkar beside them.

In his suicide note, Rohith wrote: "My birth is my fatal accident. I can never recover from my childhood loneliness. The unappreciated, unacknowledged child from my past." He concluded with what became a rallying cry: "The value of a man was reduced to his immediate identity and nearest possibility. To a vote. To a number. To a thing."

Three years and four months later, on May 22, 2019, Dr. Payal Tadvi was found hanging in her hostel room at BYL Nair Hospital in Mumbai. She was 26 years old, a second-year resident doctor in gynaecology, the first woman from the Tadvi Bhil tribal community to pursue post-graduation. For over a year, three upper-caste senior doctors had subjected her to what a 1,203-page police chargesheet would document as relentless harassment. They used casteist slurs, taunted her about her "quota" admission despite her NEET scores, excluded her from surgeries, and threw files at her for "shoddy" work. Hours before her death, she called her mother to say she could no longer bear the torture.

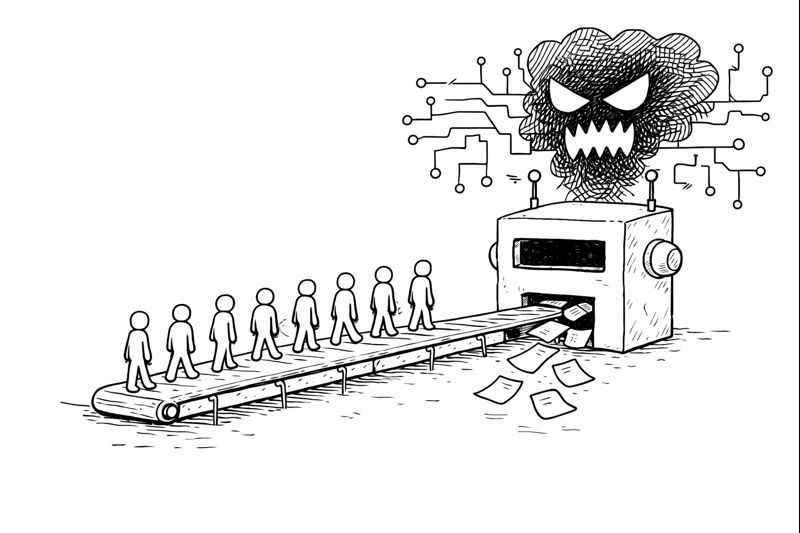

Each AIIMS doctor represents roughly Rs 1.7 crore in public investment over their training. Payal's death destroyed that investment and the decades of productivity her career would have generated. She is one data point in what amounts to thousands of crore rupees in annual human capital destruction through discrimination-driven dropouts and suicides at elite institutions. India invests heavily in creating talent at IITs, AIIMS, and central universities, then systematically destroys that talent through institutional hostility that makes marginalised students calculate whether the psychological cost of studying in hostile environments is worth the promise of mobility that higher education supposedly offers.

The economic architecture of this destruction runs deeper than individual tragedies. SC workers earn approximately 30% less than upper-caste workers in regular salaried employment, with discrimination accounting for one-third of that wage gap while the remainder reflects differences in education and skills. The cost of being SC in Indian labour markets has increased from 24.3% underpayment in 2004-05 to 26.3% in 2017-18. Field experiments show that Dalit applicants have 33% lower odds of receiving employer callbacks than upper-caste applicants with identical qualifications. World Bank research estimates caste-based labour market segmentation reduces India's per capita GDP by 1.5-2% annually, translating to approximately Rs 5-6.6 lakh crore in foregone output based on current GDP levels.

Against this economic backdrop, India allocates approximately Rs 80,000 per institution per year on equity mechanisms through honoraria for Equal Opportunity Cell coordinators and advisors, volunteer stipends attached to existing faculty roles rather than dedicated enforcement capacity.

On January 29, 2026, exactly ten years and twelve days after Rohith's death, these two stories converged in the Supreme Court of India. The mothers of both students, Radhika Vemula and Abeda Salim Tadvi, had petitioned the court in 2019 seeking mechanisms to end caste-based discrimination on campuses. The University Grants Commission responded by drafting new regulations. But when those regulations were finally notified on January 13, 2026, they triggered something nobody anticipated: a political earthquake that has the Bharatiya Janata Party facing resignations from its own cadre, protests across its strongholds, and a Supreme Court stay that called the regulations "vague," "capable of misuse," and likely to have a "dangerous impact" on society.

What connects two student suicides to a governing party's political crisis reveals something more troubling than bad policy drafting. It exposes the fundamental impossibility of the BJP's caste politics and the cynicism with which institutions treat the deaths of marginalised students as opportunities for political calculation rather than moments demanding structural reform.

This contradiction has deeper roots than contemporary coalition management. The RSS was founded on September 27, 1925 by Keshav Baliram Hedgewar, a Deshastha Brahmin, alongside fellow Brahmins in Nagpur. The timing mattered: B.R. Ambedkar's Chavdar Lake Satyagraha (1927) and Kalaram Temple entry movement (1932) threatened Brahmin social dominance in Maharashtra. As political scientist Christophe Jaffrelot documents, the RSS served dual purposes from its founding: mobilizing against Muslims while co-opting lower-caste discontent under upper-caste leadership. B.S. Moonje, Hindu Mahasabha leader and RSS patron, praised the organization in 1925 for "instilling discipline among Hindus" and noted with satisfaction that "even the lower orders are now joining the daily drill." Five of six RSS chiefs across a century have been Brahmins. No Dalit, OBC, or Adivasi has ever held the top position.

The ideological framework makes genuine cross-caste solidarity structurally impossible. M.S. Golwalkar, who led RSS from 1940 to 1973, provided explicit theological justification for caste hierarchy in his 1966 text Bunch of Thoughts: "Brahmin is the head, Kshatriya the hands, Vaishya the thighs and Shudra the feet." In a 1969 interview with the Marathi daily Nava Kal, he stated: "Varna system is the creation of God, and that cannot be destroyed, even if man tries to undo it." The RSS chose "samarasata" (harmony preserving hierarchy) over "samata" (equality), explicitly rejecting Ambedkar's call for caste annihilation. Bhanwar Meghwanshi, a former RSS Dalit member, documents experiencing this in practice: when he expressed a desire to become a pracharak, his upper-caste superior told him he should "be content with being a vistarak (propagator)" given his background. When he prepared food for members of the Sangh Parivar visiting his district, they refused to eat at his home and then threw the food onto the road.

The BJP inherited this structural contradiction: upper-caste organisational dominance requiring lower-caste electoral support. The Print's 2018 analysis found approximately 75% of national BJP office-bearers came from upper castes. Yet the party's coalition depends on lower-caste votes: 42% of OBCs and 33% of Dalits voted BJP in 2019. The 2024 Lok Sabha results exposed this fragility when the BJP lost 19% of Koeri-Kurmi (OBC) votes and 13% among other OBCs, reducing its seat tally in UP alone from 62 to 33. The opposition's "400 paar" campaign, warning that the BJP would abolish reservations, resonated precisely because the RSS's documented ideological opposition to affirmative action made the threat credible.

The January 2026 UGC crisis is not a policy miscalculation but the century-old founding contradiction surfacing again: an organisation built on preserving Brahminical hierarchy cannot genuinely accommodate lower-caste demands for structural equality without abandoning its ideological foundations.

From Advisory to Enforceable: The Evolution Nobody Wanted

The 2012 UGC regulations on equity were toothless by design. They recommended that universities establish Equal Opportunity Cells to address discrimination against SC and ST students. These cells were advisory rather than mandatory. They had no enforcement mechanism, no fixed timelines for investigating complaints, and no consequences for institutions that ignored them. When Rohith Vemula and four other students were suspended in 2015, the University of Hyderabad had an Equal Opportunity Cell. It did not save him.

The regulatory vacuum was clear. The Sukhadeo Thorat Committee findings on AIIMS documented rampant caste bias in premier institutions. Government data submitted to Parliament in December 2021 revealed that 122 students across IITs, IIMs, and NITs died by suicide between 2014 and 2021, with approximately 56% from SC, ST, and OBC backgrounds. The 2012 regulations mentioned ragging (cross-referencing the 2009 UGC anti-ragging regulations) but did not mention OBCs in the scope of caste-based discrimination. There was no specification about committee composition, no mandated response timelines, and no accountability for administrative inaction.

After Rohith and Payal's deaths, the Supreme Court took note. In the Abeda Salim Tadvi v Union of India case filed in 2019, the court directed the UGC to create a "very strong and robust mechanism" to tackle campus discrimination. In September 2025, the court gave specific directions: address discriminatory practices, prevent segregation, ensure timely scholarship disbursal, and create effective grievance redressal systems.

In February 2025, the UGC published draft regulations inviting public feedback. The draft did not include OBCs in the definition of caste-based discrimination. It also included provisions for penalising false complaints. In December 2025, the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Education, chaired by Congress MP Digvijaya Singh, intervened. The committee recommended expanding protections to include OBCs, who constitute over 40% of students in higher education.

On 13 January 2026, the UGC notified the final regulations. The changes from draft to final version were significant:

What changed: The final regulations defined "caste-based discrimination" under Regulation 3(c) as discrimination "only on the basis of caste or tribe against the members of the scheduled castes, scheduled tribes, and other backward classes." They mandated Equal Opportunity Centres (not just advisory cells) with Equity Committees of 10 members, at least five from SC/ST/OBC categories, women, and persons with disabilities. They established 24×7 helplines, required Equity Committees to meet within 24 hours of receiving a complaint, mandated that investigation reports be submitted within 15 days, and required action within 7 days. They empowered the UGC to impose punitive action, including debarment from schemes, funding cuts, and withdrawal of permission to offer new programs.

What disappeared: The provision for penalising false complaints, present in the February 2025 draft, was removed. Any mention of ragging, which the 2012 regulations had cross-referenced, was gone. There was no specification for representation or grievance mechanisms for general category students in the equity framework.

The regulations were notified under the leadership of Jagdish Kumar, the former JNU Vice Chancellor with documented ties to RSS-affiliated organisations, who was appointed UGC chairman in 2022. Within days, protests erupted across the country.

The Economics of Institutional Failure

Behind the regulatory language lies a staggering pattern of economic waste. The government spends approximately Rs 5.2 lakh annually per IIT student, with students paying around Rs 2 lakh in fees, yielding a public subsidy of over Rs 3 lakh per year. Yet 63% of undergraduate dropouts from the top 7 IITs come from reserved categories (SC/ST/OBC), despite these groups comprising 49.5% of admissions. Over 2019-2023, IITs recorded 8,139 total dropouts, with 3,542 (43.5%) from reserved categories.

The geographic and institutional disparities are extreme. IIT Guwahati recorded the worst disproportion: 88% of its dropouts came from reserved categories. IIT Roorkee's 2015 mass dismissal affected 90% of students from SC/ST/OBC backgrounds, who were dismissed for low grades. At IIT Bombay, 70% of students with CPI below 5 come from SC/ST backgrounds, while General/OBC students typically achieve CPIs of 6-9.

These dropouts represent destroyed investments. Using human capital accounting methods that calculate the present value of lifetime earnings, the annual economic loss is substantial. Parliamentary data shows approximately 1,600 reserved category students drop out from IITs annually, with another 3,500 from central universities. Combined with medical college attrition and the 17-18 annual suicides at elite institutions, the total human capital destruction runs into thousands of crore rupees each year. This excludes foregone tax revenue, productivity spillovers, and the intangible costs of wasted potential.

Suicide data, though systematically underreported, reveals similar patterns. From 2014-2021, elite institutions (IITs, NITs, IIMs) recorded 122 suicides, with SC, ST, and OBC students accounting for 56% of these deaths. The government admits it maintains "no official data on linkages between caste-based discrimination and suicide rates among SC/ST students," a deliberate blind spot that prevents accountability.

The academic performance gaps that precede dropouts are not explained by preparation alone. Research tracking cohorts from the 1950s through 1989 shows SC sons closed 50% of the mobility gap with higher castes between the 1960s and 1980s cohorts, rising from the 33rd-35th percentile to the 38th percentile in intergenerational economic mobility. Natural experiments examining groups newly added to SC lists in 1977 found they experienced a 7-8 percentile rank increase in upward mobility over 20 years, approximately equal to the gap that later opened between Muslims and SCs. This evidence suggests that reservations in education and employment substantially drive mobility gains when institutional environments do not actively sabotage them.

Muslims present a counter-example. Their mobility declined over the same period, and they now have worse outcomes than both SCs and STs. This deterioration occurred without equivalent affirmative action coverage and amid rising discrimination.

The pattern is clear: when institutions actually function, affirmative action works. Brazil's experience offers direct evidence. After implementing explicit racial quotas in federal universities in 2012, affirmative action students performed well academically. GPAs showed minimal differences from non-affirmative action students by graduation. Performance gaps in competitive programs largely disappeared by graduation. This evidence directly contradicts "quality dilution" arguments against reservation.

India's institutional environment produces the opposite outcome. The economics literature documents persistent labour market penalties. SC workers earn approximately 30% less than upper-caste workers in regular salaried employment, even after controlling for education and skills, with discrimination accounting for one-third of this wage gap. The employment gap tells an even starker story: while discrimination explains 14% of the employment gap in public-sector jobs, it accounts for 53% of the gap in private-sector employment. A "glass ceiling effect" emerges at higher wage levels, where SC employees face the steepest discrimination at the 90th percentile of earnings.

The hiring discrimination data is stark. Dalit applicants have 33% lower odds of receiving employer callbacks than upper-caste applicants with identical qualifications. Occupational segregation compounds these penalties: SC representation in Group A and B government positions (senior administrative roles) remains low, while the vast majority of SC government employees occupy Group C and D positions. In IITs and IIMs as of 2018, SC/ST faculty comprised only 2.5% and 1.5% of the total faculty pools, respectively, despite the mandated 22.5% reservation, though these figures have improved somewhat in recent years. Fifteen IITs had zero ST faculty members.

This faculty composition matters economically because it shapes who mentors students, who designs curricula, and who serves on the grievance committees meant to address discrimination. Among 45 Central Universities, only 1 SC Vice-Chancellor, 1 ST Vice-Chancellor, and 5 OBC Vice-Chancellors hold office. When 98% of professors at top 5 IITs plus IISc come from privileged castes, the institutional culture that drives dropout and suicide becomes structurally embedded rather than individually aberrant.

Four Questions the Supreme Court Should Not Have Needed to Ask

On 29 January 2026, a bench of Chief Justice Surya Kant and Justice Joymalya Bagchi heard three writ petitions challenging the regulations. The petitions were filed by Mrityunjay Tiwari, a post-doctoral researcher at Banaras Hindu University, advocate Vineet Jindal, and Rahul Dewan. What unfolded in court was extraordinary, not for what the petitioners argued but for what the Supreme Court itself identified as fundamental drafting failures.

The court framed four questions:

First: Why does Regulation 3(c) separately define "caste-based discrimination" when Regulation 3(e) already provides a comprehensive definition of "discrimination"? Regulation 3(e) defines discrimination as "any unfair, unjust, or biased or differential treatment, whether direct or indirect, explicit or implicit" based on "caste, religion, race, gender, place of birth, disability, or any of them." If this covers all forms of discrimination, what rational purpose does a separate, narrower definition serve that limits caste-based discrimination only to discrimination against SC/ST/OBC members?

"We are looking to create a free and equitable atmosphere in universities," Justice Bagchi asked. "We find no reason why 3(e) is subsisting as it was; how does 3(c) become relevant? Is it a redundancy?"

Second: What about the word "segregation" in Regulation 7(d)? This clause directs institutions "to ensure that any selection, segregation, or allocation for the purpose of hostels, classrooms, mentorship groups, or any other academic purposes is transparent, fair, and non-discriminatory." The court wondered if this was inadvertently mandating caste-based segregation in classes and hostels, violating the constitutional spirit of fraternity. "Are we going backwards from whatever we gained in terms of achieving a casteless society?" CJI Kant asked.

Third: Why is ragging completely absent from the 2026 regulations? The 2012 regulations had referenced ragging in the context of harassment. The 2009 UGC anti-ragging regulations remain in force separately. But the 2026 equity regulations, designed to address campus discrimination comprehensively, make no mention of it. One petitioner illustrated the gap with a hypothetical: "I am a General Category fresher, and my senior comes to rag me. If I oppose ragging, then I can face anti-discrimination charges." The senior happens to be from SC/ST. Under the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, there is no provision for anticipatory bail. The fresher's career ends on the first day of college.

Fourth: Where are the safeguards against misuse? The February 2025 draft had included penalties for false complaints. The final January 2026 regulations removed this provision entirely. There is no mechanism to protect students or faculty from malicious accusations. There is no requirement for evidence before investigation. There is no protection against the weaponisation of the grievance system.

The language the Supreme Court used matters. The bench called the regulations "prima facie vague," "capable of misuse," and warned of "very sweeping consequences" with a "dangerous impact." CJI Kant told senior advocate Indira Jaising, who was defending the regulations: "There are 4-5 questions, this will have very sweeping consequences, dividing society, will lead to a very dangerous impact."

The court issued notice to the Union government and UGC, returnable on 19 March 2026. It ordered that the 2026 regulations be kept "in abeyance." Using its plenary powers under Article 142 of the Constitution, it directed that the 2012 regulations would continue in force until further orders.

We are back where we started. Back to the advisory, toothless framework that could not protect Rohith Vemula or Payal Tadvi. The Supreme Court suggested forming a committee of "eminent jurists" to redraft the regulations, people who understand social values and the ailments society is facing."

The question nobody in court seemed willing to ask: if regulations emerging from a Supreme Court-mandated process, drafted over years with stakeholder consultations, overseen by a parliamentary committee, require this level of judicial scepticism and redrafting, what does that say about the institutional capacity to actually address the problem?

When Your Core Voters Send You Bangles

The regulatory failures might have remained an academic debate in legal circles. What turned them into a political crisis was timing, geography, and the mathematics of caste.

Between 13 January, when the regulations were notified, and 26 January, Republic Day, protests exploded across Uttar Pradesh. Not in opposition strongholds. In BJP bastions. Deoria, Gorakhpur, Varanasi, Meerut, Bareilly, Prayagraj, Jaunpur, Lucknow. Cities that voted overwhelmingly for the BJP in 2014, 2017, and 2019. Cities that began deserting the party in 2024.

In Lucknow, 11 BJP functionaries resigned from the party in protest.

In Bareilly, City Magistrate Alankar Agnihotri, a 2019-batch Provincial Civil Service officer, resigned and was subsequently suspended. In Rae Bareli, BJP leaders sent bangles to upper-caste MPs and MLAs, a traditional insult questioning their courage for not opposing the regulations. In Kaushambi, a protester wrote a letter to Prime Minister Modi using his own blood.

The geography matters. These are not cities with a history of anti-BJP politics. Gorakhpur is Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath's parliamentary constituency. Varanasi is Modi's. Bareilly returned BJP candidates with comfortable margins in both the 2017 and 2019 state elections. These protests were happening in the party's core territories, among the voters the BJP has historically counted on without question.

The caste arithmetic matters too. BJP lost over 60 Lok Sabha seats in Uttar Pradesh in 2024. The coalition between the Samajwadi Party and Congress managed to consolidate OBC and Dalit votes in ways that fractured the BJP's electoral dominance. Now, with UP panchayat polls looming and assembly elections scheduled for 2027, the party faces a calculation it cannot resolve. It needs OBC votes, which now constitute the majority across the Hindi belt. It also requires an upper-caste organisational base that provides the resources, networks, and ground-level workers that keep the party machinery functioning.

The regulations put these two imperatives in direct conflict. When Nishikant Dubey, a senior BJP MP, felt compelled to issue clarifications on social media, his language revealed the bind. He invoked Articles 14 and 15, emphasized the 10% Economically Weaker Sections quota secured by the Modi government, and gave "Modi's guarantee" that no discrimination would occur against general category students. The defensive posture itself was telling. The party that built its dominance on aggressive majoritarian politics was now scrambling to reassure its own supporters that they would not be victimized.

Education Minister Dharmendra Pradhan promised safeguards against misuse but ruled out any rollback. The message was clear: the government would not reverse course but would try to manage the political fallout through rhetoric and damage control.

The Impossibility of the BJP's Caste Politics

What the UGC equity regulations reveal is not just a policy failure but a fundamental contradiction at the heart of the BJP's social coalition. The party needs OBC votes to win elections. It needs upper-caste organisational capacity and resources to run elections. It needs Dalit votes to cross thresholds in certain constituencies. It needs RSS ideological support and ground-level mobilisation. Each of these groups has incompatible interests regarding caste equity.

For upper castes, any expansion of institutional protection for SC/ST/OBC students feels like an attack on meritocracy and a threat to their children's futures. For OBCs, inclusion in anti-discrimination frameworks is recognition of their historical marginalisation and contemporary vulnerability. For SCs and STs, equity regulations are insufficient half-measures when what they face is not just discrimination but what Babasaheb Ambedkar called graded inequality.

The BJP's attempt to straddle these contradictions produces policy schizophrenia. Jagdish Kumar, the UGC chairman who oversaw the drafting of these regulations, is the former JNU Vice Chancellor with ties to RSS-affiliated organisations who presided over one of the most politically fraught periods in that university's history. Kumar's appointment to lead the equity regulations process sent a message to the RSS base. The regulations themselves, particularly after the Parliamentary Standing Committee intervention to include OBCs, sent another message to OBC constituencies.

Neither message satisfied anyone. The regulations were simultaneously too weak to protect students like Rohith Vemula and Payal Tadvi and too strong for upper-caste voters who saw them as discriminatory. They failed to address ragging, failed to specify safeguards against misuse, and failed to create mechanisms that marginalised students would actually trust. But they succeeded in one thing: exposing the limits of BJP's caste politics.

The party cannot credibly claim to champion both social justice for historically oppressed castes and the anxieties of upper-caste voters who view any institutional recognition of caste discrimination as reverse discrimination. It cannot simultaneously position itself as the party of Ambedkar (as it attempted during the 2024 Lok Sabha campaigns) and the party that protects upper-caste interests from what they perceive as quota raj. The regulations made these contradictions visible in ways that abstract political rhetoric could paper over.

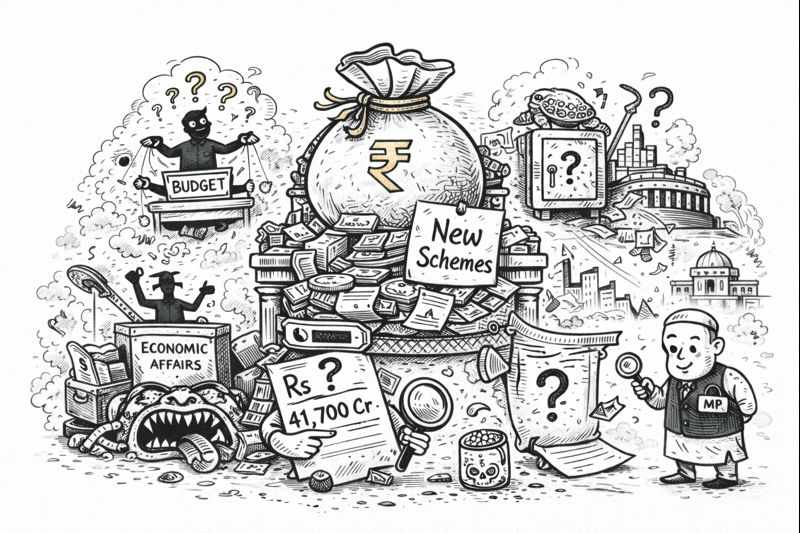

The Rs 12 Lakh Crore Allocation Gap

The political theatrics obscure a starker reality: India's fiscal commitment to SC/ST welfare dramatically underperforms its own guidelines. The cumulative gap between Scheduled Caste Sub-Plan/Tribal Sub-Plan targeted allocations and amounts actually due totals Rs 12.13 lakh crore over FY 2019-20 to 2024-25 (Rs 8.13 lakh crore for SCs plus Rs 4 lakh crore for STs), approximately one-fourth of an entire year's Union Budget.

Current allocations for equity mechanisms remain minimal. UGC's total budget for 2025-26 is Rs 3,336 crore (up 33% from the previous year). Free Coaching for SC/OBC receives Rs 20 crore total. SHREYAS scholarship umbrella gets Rs 472 crore. Post-Matric Scholarship for SC receives Rs 6,350 crore.

CAG audits reveal systematic implementation failures. A performance audit of Post-Matric Scholarships across five states found 18.58 lakh students waited 1-6 years for disbursement. Financial irregularities totalled Rs 581.68 crore; data discrepancies another Rs 455.98 crore. In Jharkhand, 34% of tested beneficiaries showed deviations, including ghost and fake entries.

Multiple flagship schemes show 20-50% underspending between Budget Estimates and Revised Estimates. PM-USHA (higher education) saw a 51% gap; Student Financial Aid saw a 33% gap. These patterns suggest that allocations exist more as political signalling than as operational commitments.

The transaction costs of current grievance mechanisms are hidden but substantial. UGC data submitted to the Supreme Court reveals that Equal Opportunity Cells and SC/ST Cells received 1,160 complaints across 704 universities and 1,553 colleges from 2019 24. The official "resolution rate" of 90.68% conceals dysfunction: most cells "function under administrative control and lack decision-making powers," with members nominated by the same administration who are then complained about.

No public data exists on average time-to-resolution, breakdown of "resolution" types (formal action versus dismissal versus informal settlement), or complainant satisfaction rates. Pending cases rose from 18 in 2019-20 to 108 in 2023-24, a 500% increase, suggesting a growing backlog despite claimed high resolution rates.

The principal-agent problems are structural. Among 45 Central Universities, only 1 SC Vice-Chancellor, 1 ST Vice-Chancellor, and 5 OBC Vice-Chancellors hold office. Leadership positions remain dominated by privileged castes. This creates fundamental conflicts: institution heads have incentives to minimise recorded discrimination rather than address it. The Thorat Committee (2007) found AIIMS authorities were "encouraging hostile caste discrimination," meaning the monitors were perpetrators.

Comparative analysis reveals India's underinvestment. The U.S. Office for Civil Rights operates with a $140- $ 162 million budget and 562 full-time staff members to handle approximately 10,000 annual complaints from institutions receiving federal funding. India's equity mechanisms are funded through honoraria of Rs 80,000 per institution per year (Rs 50,000 for advisors, Rs 30,000 for coordinators), with volunteer stipends attached to existing faculty roles rather than dedicated enforcement capacity.

Using ILO labor inspectorate benchmarks (1 inspector per 10,000 workers for developed systems), India's 4.3 crore higher education students would require approximately 4,300 dedicated equity enforcement personnel. At average government salaries, this would cost Rs 2,580-3,440 crore annually. Current spending is a fraction of 1% of this figure.

The economics are straightforward. India loses thousands of crore rupees annually in human capital destruction from discrimination-driven attrition at elite institutions alone. Proper equity infrastructure might cost Rs 2,500-3,500 crore, a potential ROI of multiple times over if effective prevention reduced even half of the current losses. World Bank estimates that caste-based labour market segmentation reduces India's per capita GDP by 1.5-2% annually, translating to Rs 5-6.6 lakh crore in foregone output.

Current spending on equity enforcement is perhaps Rs 50-100 crore across all higher education institutions, representing less than 2% of what effective infrastructure would require and less than 1% of the cost of discrimination. This is not a resource-constrained problem; India allocates Rs 11,349 crore to IITs alone in the 2025-26 budget. It is a political economy problem where organised upper-caste interests capture regulatory processes while SC/ST communities lack equivalent organisational power to demand implementation.

What Gets Lost in Political Calculation

Rohith Vemula was not driven to suicide by university administration alone. He was driven to suicide by a system where Bandaru Dattatreya, a union minister, wrote letters to the Human Resources Development Ministry labeling the Ambedkar Students Association as anti-national, where Vice Chancellor Appa Rao implemented suspensions that violated university procedures, where equal opportunity cells existed on paper but offered no protection, where his fellowship was stopped at a moment when he had no other means of support.

Payal Tadvi was not driven to suicide by three senior doctors alone. She was driven to suicide by a department head who received complaints and did nothing, by a hospital administration that prioritized protecting accused doctors over investigating harassment, by a medical education system where the Indian Medical Association president told The Wire there is no caste discrimination in the Indian medical field even as a 1,203-page chargesheet documented systemic abuse, by a professional culture where upper-caste doctors believe talent is synonymous with caste privilege.

The 2026 regulations would not have saved either of them. The regulations create grievance mechanisms, but grievance mechanisms require faith that complaints will be heard, that investigations will be fair, that perpetrators will face consequences. When Payal's mother wrote to BYL Nair Hospital in December 2018 and again in May 2019, she was using the existing grievance mechanism. It failed. When Rohith Vemula and other students protested their suspension, they were using the existing grievance mechanism. It failed.

The new regulations change the name from Equal Opportunity Cells to Equal Opportunity Centres. They add timelines and penalties. They specify committee composition. But they do not change the fundamental power dynamic that makes a Dalit student vulnerable to institutional indifference and upper-caste impunity.

Payal Tadvi's mother wrote to BYL Nair Hospital months before her daughter's death, detailing the harassment. She witnessed it firsthand when she visited Payal at work. The hospital had an anti-ragging committee, a grievance cell, and an administration. None of them saved Payal because none of them believed her mother. Or if they believed her, they calculated that protecting the careers of three upper-caste doctors was more important than protecting the life of one tribal student.

This is what gets lost when equity regulations become political ammunition: the actual question of whom institutions believe, whom they protect, and whom they sacrifice. The 2026 UGC regulations failed not because they were too strict on general category students but because they tried to address institutional discrimination through individual complaints. They failed because they assumed that if you mandate committee composition and timeline compliance, you can engineer equity. They failed because they were drafted by people who understand legal frameworks but do not understand the lived experience of walking into a classroom or operation theater or hostel room where everyone knows you are there because of your caste and assumes you are less competent because of it.

The regulations that the Supreme Court stayed on January 29, 2026, might be revised and renotified by eminent jurists who understand social realities. Those revised regulations might avoid constitutional pitfalls and political backlash. They will still not save the next Rohith Vemula or Payal Tadvi because you cannot regulate away structural violence. You cannot mandate institutional culture through committee composition. You cannot timeline your way to dignity.

Universities still have Equal Opportunity Cells that exist largely on paper. Complaints still go uninvestigated. Perpetrators still face no consequences. Students from marginalised communities still have to calculate whether the psychological cost of studying in hostile environments is worth the promise of social mobility that higher education supposedly offers.

Until Indian institutions, from universities to hospitals to government offices, actually believe that a Dalit student or tribal doctor is a student or doctor first, and not a quota-filler whose presence requires constant justification, equity regulations will remain what they have always been: elaborate bureaucratic rituals performed so the state can say it did something while students keep dying.

The 2024 election demonstrated the electoral salience of reservation protection. BJP's "400+ seats" slogan backfired when the opposition framed it as an intent to eliminate reservations. The SP-Congress alliance won 43 UP seats versus the BJP's 33 by consolidating SCs, OBCs, and Muslims around reservation protection. The question is whether this electoral signal translates into investment in enforcement infrastructure or remains a symbolic commitment undermined by systematic underfunding and regulatory capture.

Brazil achieved effective affirmative action through "attention to material interests and electoral incentives." After implementing explicit racial quotas in federal universities in 2012, students of colour who received affirmative action performed well academically, with GPAs showing minimal differences from non-affirmative action students by graduation. India's constitutional framework provides stronger formal protections than those of any comparable democracy. What's missing is the fiscal and institutional commitment to make rights real.

Radhika Vemula and Abeda Salim Tadvi went to the Supreme Court seeking justice for their children's deaths and protection for other students. They got regulations that became a political crisis, a constitutional challenge, and evidence of state incapacity. Their children are still dead. Other students are still vulnerable. Indian institutions remain adept at producing paperwork while avoiding accountability.

Further Reading

On caste discrimination in universities:

Rohith Vemula's suicide note, The Hindu

Beyond Statistics: The Link Between Institutional Caste Discrimination and Student Suicides in India, The Wire

Stress, dropouts, suicides: Unravelling IIT's casteism problem, Newslaundry

On labour market discrimination and economic costs:

Scheduled Castes in the Indian Labour Market, NewsClick

The Grammar of Caste: Economic Discrimination in Contemporary India, Thorat and Newman

Intergenerational Mobility in India: New Measures and Estimates, Asher, Novosad, and Rafkin, American Economic Journal (2024)

The macroeconomic costs of the caste system in India, VoxDev

On BJP's caste politics:

Supreme Court raises 4 questions on UGC equity regulations 2026, LiveLaw

Resignations, Protests, Petitions: BJP Faces Fire From Upper Caste Groups, The Wire

On the regulations and implementation:

UGC (Promotion of Equity in Higher Education Institutions) Regulations, 2026 (official gazette notification)

Supreme Court stays 2026 UGC equity regulations, Supreme Court Observer

CAG Performance Audit on SC/ST Scholarships, Comptroller and Auditor General of India

Varna is a development economist and writes at policygrounds.press

Write a comment ...