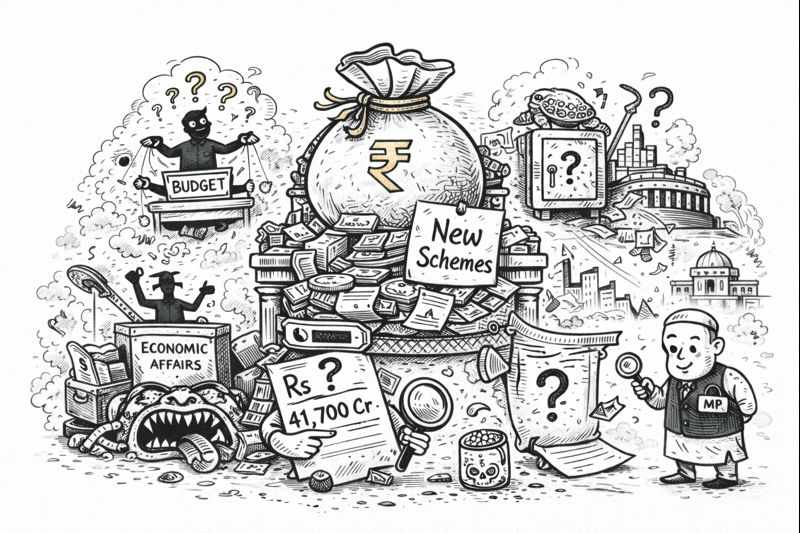

Budget 2026-27 allocated Rs 250 crore for "Orange Economy" labs to train 2 million AVGC workers by 2030. South Korea invests $1.1 billion annually in content production and IP development, building companies like CJ Entertainment that own global franchises. India's approach trains animators to execute Hollywood's visions while Adani-Ambani extract public wealth through airports and telecom, not creative industries. The orange branding masks saffron reality: metrics without investment, training without capacity.

I've watched India's "innovation ecosystem" up close. Four years running a stage-zero innovation incubator for the social sector, solving for really "wicked problems", taught me what actual development research infrastructure looks like. When I see the Budget 2026-27 Orange Economy announcement proposing AVGC Content Creator Labs in 15,000 schools to train 2 million professionals by 2030, I immediately recognise the pattern. New metrics (students trained, labs built), zero investment in what actually matters (production financing, IP creation, value capture).

The numbers tell you everything. India's AVGC sector employs 260,000 workers, generating $2.5-3 billion annually. Roughly 70% of that revenue comes from outsourced work for Hollywood. Indian VFX artists contributed to Oscar-winning work on Dune, Inception, and Interstellar. The IP belongs entirely to the studios that commissioned the work. India executes, Hollywood owns. The government's response to this structural dependency is to train more executors.

Meanwhile, South Korea invests $1.1 billion annually in its content sector, funds production directly through cash rebates and loans, protects its domestic market through screen quotas, and has built companies like CJ Entertainment that own Korean IP and capture franchise value globally. China spent decades transitioning from an animation sweatshop to an IP owner, producing companies like miHoYo (valued at $23 billion) that created Genshin Impact ($4.1 billion in lifetime revenue). India allocates Rs 250 crore ($29 million) to train workers for other people's creative visions.

The Orange Economy Announcement: Training Without Transformation

Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman's Budget 2026-27 identified the AVGC sector as requiring 2 million professionals by 2030. The government's response: establish Content Creator Labs in 15,000 secondary schools and 500 colleges, coordinated by the Indian Institute of Creative Technologies (IICT) in Mumbai. The initiative receives Rs 250 crore (approximately $29 million), a new budget line with no prior allocation.

The stated objectives focus exclusively on workforce development: hands-on training in animation, VFX, gaming, digital production, and extended reality technologies. Information and Broadcasting Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw framed this as a job-creation initiative, promising "20 lakh new jobs." The government also announced a new National Institute of Design in eastern India through a "challenge route" competitive selection among states.

What's missing is everything that creates value. The budget provides no production subsidies, tax credits for content creation, co-production financing, IP development funds, or market protection measures. The Rs 250 crore represents roughly $0.02 per Indian citizen for the development of creative industries. South Korea's content investment through KOCCA alone totals $460 million, approximately 16 times India's entire AVGC allocation. Korea's total 2026 cultural sector budget is $1.1 billion, a 27% increase from 2025. India allocated $29 million.

India's AVGC Reality: Executing Hollywood's Creative Visions

The business model of the Indian AVGC sector is unambiguous. DNEG CEO Namit Malhotra stated explicitly: "More Indian VFX artists work on Hollywood films than Indian films." DNEG India employs over 10,000 workers across Mumbai, Hyderabad, Chennai, and Bangalore, contributing to Oscar-winning visual effects. Prime Focus worked on Gravity, MPC's Bangalore facility devoted 1,000+ artists to The Jungle Book, completing 1,200 shots over two years.

This work, while technically excellent, follows a consistent pattern. Indian artists receive functional instructions rather than creative briefs. Academic research describes the workflow: Hollywood studios send "animatics" (animated storyboards), asset specifications, and technical requirements via fibre optic cable. Indian teams execute the technical work, return files for review, and iterate until approval. The IP ownership is explicit: work-for-hire contracts ensure all intellectual property belongs to the commissioning studio.

When the industry contracted 9% in FY 2024 due to Hollywood strikes, the dependency became undeniable. Indian studios idled capacity, laid off workers, and waited for international commissions to resume. The sector's vulnerability to external production decisions reveals its structural position: supplier, not creator.

Original Indian IP remains marginal. Green Gold Animation's Chhota Bheem franchise stands as the rare exception—a domestically created animated property with successful merchandising. But the industry's own assessment is blunt: "The AVGC sector in general has suffered a lack of original Indian intellectual property as most work in this sector is outsourced."

The Gaming Paradox: 500 Million Players, Zero Global Franchises

India is the world's largest mobile gaming market by downloads, with 488-591 million gamers in 2024, accounting for 18-20% of global players and 8.45 billion annual downloads (the highest globally). Yet India captures merely 1.1% of global gaming revenue ($3.7-5 billion versus $324 billion worldwide).

The games Indians play are overwhelmingly foreign: Battlegrounds Mobile India (Krafton, Korea), Free Fire (Garena, Singapore), Coin Master (Moon Active, Israel), and Clash of Clans (Supercell, Finland). Shooter games alone capture 50% of all in-app purchase revenue. India downloads Indian games but spends money on foreign ones. Ludo King achieved 1 billion downloads but generates perhaps $20-30 million annually. PUBG Mobile's lifetime revenue exceeds $9 billion.

The Indian game development industry functions primarily as a service outsourcer. Lakshya Digital has contributed to 175+ AAA titles, including Bloodborne, Sea of Thieves, and Palworld. Rockstar India (through its acquisition of Dhruva Interactive) has worked on GTA V, Red Dead Redemption, and Max Payne 3. Ubisoft India employs 1,300+ people supporting Assassin's Creed Valhalla and Far Cry 6. These studios excel at asset development, animation, and quality assurance. Creative direction and IP ownership remain with foreign parent companies.

Why no Indian AAA games or global franchises? The capital requirements are prohibitive ($ 50-150+ million for AAA development), Indian investors lack precedent for such bets, and 83-85% of India's gaming revenue comes from real-money gaming (fantasy sports, rummy, poker), not video games. Nazara Technologies, India's only publicly listed gaming company, derives most of its revenue from acquisitions such as Kiddopia (educational games) and Nodwin (esports), rather than from original IP development.

Korea Built IP-Owning Companies, Not Training Programs

South Korea's transformation from cultural importer to global entertainment exporter followed a deliberate, multi-decade strategy that was fundamentally different from India's approach. The Korean government recognised cultural industries as strategic economic assets after the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis—not as job programs, but as IP-generating export industries.

Government investment grew systematically: from 5.4 billion KRW ($4.1 million) in 1994 to 100 billion KRW ($76.9 million) by 1999 to the current content sector budget of 1.617 trillion KRW ($1.1 billion). KOCCA operates with a 609 billion KRW ($460 million) budget specifically for content development, including targeted allocations for broadcasting/video (980 billion KRW) and games (632 billion KRW).

Market protection mechanisms were central. Korea's screen quota required theatres to show Korean films for 146 days annually (later reduced to 73 days for the US-Korea FTA), ensuring domestic content reached audiences. Broadcast regulations limited foreign content: foreign shows were restricted to 20% of prime time on terrestrial networks. These protections allowed Korean content to develop without being overwhelmed by American imports.

The government funded the production directly. The Korean Film Council provides up to 30% cash rebates for productions filmed in Korea, loans of up to 600 million won ($460,000) per film to cover 50% of production costs, and maintains a cinema fund totalling approximately $430 million. OTT content production support received a 168% budget increase to 123.5 billion KRW ($95 million).

Private conglomerates built vertically integrated studios controlling the entire value chain. CJ Entertainment (now CJ ENM) evolved from Samsung's multimedia division into a company that controls investment, production, distribution, exhibition (the CGV multiplex chain), and international sales, and has produced Parasite, Squid Game, and Snowpiercer. K-pop agencies like SM Entertainment and HYBE developed systematic talent pipelines, multi-year trainee investments ($500,000-$3 million per group), and IP-centric business models extending into webtoons, games, and merchandise.

The economic result: Korean cultural content exports reached $13.24 billion in 2022, surpassing secondary batteries and home appliances. K-content drives an estimated 7.5% of Korean GDP.

China's Transition from Animation Sweatshop to IP Owner

In the 1980s-90s, Shenzhen was the "city of cartoon factories," with studios painting frames for foreign storyboards at half the cost. Workers were compared to "migrant workers producing shoelaces." China executed; others owned.

The transformation accelerated through government support and private entrepreneurship. miHoYo (now HoYoverse) exemplifies the new model: founded in 2011 by Shanghai Jiao Tong University students, the company grew from 7 employees to over 1,000 and achieved a $23 billion valuation by reinvesting revenue into original IP development. Genshin Impact generated over $4.1 billion lifetime revenue with 100+ million monthly active users—designed for global markets from inception with cross-platform accessibility and localization in 14+ languages.

Black Myth: Wukong became China's first AAA single-player success: 20+ million copies sold, $1 billion revenue in its first month, and 6 years of development on a $56-70 million budget. The game's success, based on Journey to the West mythology, validated the global appeal of Chinese cultural IP.

Animation followed a parallel trajectory. Ne Zha 2 (2025) achieved $2.2+ billion global box office, surpassing Pixar's Inside Out 2 to become the highest-grossing animated film ever, produced by 138 animation companies and 4,000+ animators over 5 years. China's animation industry revenue reached 270.4 billion yuan ($37.3 billion) in 2022.

Government policy created supportive conditions: cultural industry R&D funding reached 152.9 billion yuan ($21 billion) in 2022, state-backed investment funds target IP creation, and import quotas protect domestic content (roughly 20 foreign films annually receive theatrical release). China's total cultural industry business revenue reached 16.55 trillion yuan (~$2.3 trillion) in 2022.

Orange Branding, Saffron Reality: While Announcing Creative Economy, Building Crony Capitalism

The "Orange Economy" branding is deliberate. Orange suggests creativity, modernity, global engagement, and progressive economic vision. It evokes the cultural economy, the knowledge worker, and the digital creative class. The government presents this as India embracing the future, moving beyond manufacturing deficits into high-value creative exports.

Meanwhile, the actual economy being constructed under the current government follows a different colour scheme. The "saffron economy," named for Hindu nationalism's symbolic colour, operates through systematic crony capitalism where public resources flow to politically connected oligarchs rather than productive capacity building. While the Orange Economy announcement trains students in animation software, the saffron economy privatises airports, ports, coal mines, and public sector enterprises through non-competitive processes, favouring specific business houses.

Electoral bond data revealed that the Adani and Ambani groups were among the BJP's largest corporate donors, funnelling hundreds of millions through opaque channels. In return, regulatory frameworks were rewritten midstream to benefit their businesses. Adani, with no prior airport experience, became India's largest private airport operator overnight after the government relaxed regulations and amended bidding rules. Reliance Jio received regulatory advantages that forced competitors out of the telecom market, creating a duopoly.

The scale is staggering. Gautam Adani's wealth rose from approximately $8 billion in 2014 to over $140 billion at its peak in 2022, an unprecedented increase in corporate history. This wealth accumulation did not come from technological innovation, product development, or competitive success in global markets. It came from acquiring public assets at favourable prices, securing regulatory advantages, and leveraging political connections to eliminate competition. Mukesh Ambani's net worth similarly exploded, doubling from $23 billion to $55 billion between 2016 and 2019 as Jio consolidated the telecom market with predatory pricing enabled by regulatory support.

The public bears the cost. When Adani's stock price collapsed in 2023 after Hindenburg Research reported accounting fraud and stock manipulation, the losses affected Life Insurance Corporation (LIC), State Bank of India (SBI), and millions of retail investors. Public sector institutions had been directed to purchase Adani stocks, providing the liquidity and credibility that foreign investors demanded. When the bubble burst, private gains remained with promoters while public losses fell on pensioners and depositors.

The Orange Economy announcement fits neatly into this framework. It provides nationalist branding and aspirational messaging that distracts from the underlying extraction. While the media celebrate AVGC Content Creator Labs and creative industry initiatives, airports and ports change hands through opaque processes. While students receive software training for execution-layer jobs, spectrum auctions are structured to benefit specific bidders. While ministers talk about cultural exports and soft power, public-sector research institutions go unfunded, and universities deteriorate.

The saffron economy does not oppose the orange economy. It requires it. Crony capitalism needs aspirational branding to maintain political legitimacy. It needs employment initiatives and skills training to address the jobs crisis created by capital-intensive oligopolistic industries that generate minimal employment. It needs nationalist rhetoric about India's global rise to deflect attention from wealth concentration and regulatory capture. The Orange Economy serves these purposes perfectly. It generates metrics (students trained, labs established), provides photo opportunities (ministers inaugurating facilities), and creates the appearance of youth-focused, forward-looking governance while the actual flow of public resources continues toward a small number of politically connected business houses.

From a development economics perspective, this is not just corruption. It is a structural impediment to genuine economic transformation. Countries that successfully transitioned from middle to high-income status did so by building broad-based institutional capacity, not by concentrating resources in oligopolies. South Korea's chaebol system faced challenges, but chaebols competed with one another, invested heavily in R&D, and succeeded in export markets through technological development rather than regulatory arbitrage. Chinese state capitalism channels resources to strategic industries and imposes performance requirements; companies that receive state support must deliver technological advancement and global competitiveness or risk losing access to resources.

The Indian model extracts wealth from public resources without building capacity. Airports privatised to Adani do not generate technological spillovers or research capacity. Spectrum sold to Reliance does not produce telecommunications equipment or networking technology. Mines leased without competitive bidding do not develop mining technology or mineral processing capacity. The system optimises for private profit extraction, not national capacity building.

Critically for creative industries, the saffron economy's beneficiaries are not building production companies, funding content creation, or developing IP. Adani operates airports and ports. Ambani owns telecom and retail. Neither has invested in building an Indian Pixar, a gaming studio creating global franchises, or a production house developing exportable Korean-style content. The crony capitalist model concentrates wealth but generates no innovation spillovers in creative industries or anywhere else.

The Pattern Repeats: Creative Industries and Scientific R&D

India's approach to creative industries mirrors a pattern visible in its scientific research ecosystem. In both domains, the government invests in measurable inputs (e.g., students trained, patents filed) while avoiding the costly investments that produce valuable outputs (e.g., global franchises, commercialised technologies).

India ranks 6th globally in patent applications but 39th in the Global Innovation Index. The country produces millions of STEM graduates annually, but underwhelms in translating research into commercial applications. The creative sector parallel is precise: train 2 million AVGC professionals, but provide no production financing to create content they might work on.

The underlying logic is consistent: input metrics can be achieved through relatively modest investment in education infrastructure, while output metrics require sustained, risky capital deployment with uncertain returns. Training programs produce quantifiable graduates; content production requires betting significant sums on creative projects that may fail. Patent applications can be filed cheaply; commercialising research requires decade-long development timelines and hundreds of millions in capital.

India spends 0.64% of GDP on R&D while China invests 2.65%, the United States 3.46%, and South Korea 4.96%. In absolute terms, India spent $71 billion on R&D in 2023 while China spent $723 billion. India's Budget 2026-27 allocated Rs 20,000 crore for the Research, Development and Innovation (RDI) Scheme (approximately $2.4 billion) focused on "private sector driven" initiatives rather than basic research. China's semiconductor fund alone allocated $47.5 billion in 2024.

Korea and China understood that training without production infrastructure creates dependency, not capability. A Korean animator trained through government programs could join CJ Entertainment, working on Korean IP with Korean ownership and value capture. An Indian animator trained through Content Creator Labs will most likely join an outsourcing operation executing Hollywood's creative visions—contributing skill while surrendering value.

What Actual Creative Industries Investment Requires

The evidence from Korea and China reveals what building IP-creating industries demands. None of these elements appear in India's Orange Economy announcement.

Production financing: Direct subsidies, tax credits, and rebates for original content development. Korea's Film Council provides up to 30% cash rebates; China's state investment funds participate in content production. India's Orange Economy provides training budgets, not production capital.

IP development infrastructure: Legal frameworks protecting creative ownership, enforcement mechanisms against infringement, and licensing systems enabling merchandise and derivative works. Hollywood's franchise revenues often exceed theatrical earnings: Star Wars merchandise ($42.2 billion) dwarfs its box office ($10.3 billion). Indian entertainment licensing totals just $406 million annually.

Market protection during development: Korea maintained screen quotas for decades while domestic capabilities matured. China limits foreign film imports to roughly 20 annually. India offers no protection for domestic content against foreign competition.

Distribution networks: Korea's CJ Entertainment controls production, distribution, and exhibition through the CGV multiplex chain. Indian creative companies lack comparable vertical integration.

Patient capital: AAA games require $50-150+ million and 5-7 years; animated films require hundreds of millions. Korea's government participates in film investment funds; China's state-backed cultural funds deploy billions. India's Orange Economy allocates training budgets.

Scale comparison: South Korea's 2026 content sector budget ($1.1 billion) exceeds India's entire Ministry of Information & Broadcasting allocation ($540 million). KOCCA alone ($460 million) receives approximately 16x India's AVGC Content Creator Labs funding ($29 million).

The Value Chain Trap India Has Constructed

Creative industries generate value across a chain: IP creation/development (highest value), production (medium-high), distribution/marketing (medium-high), and execution/support services (lowest). India has positioned itself definitively at the bottom.

Indian VFX companies market themselves primarily on cost savings: 50-80% cheaper than US/European rates for labour-intensive tasks such as wire removal, rotoscoping, and matte painting. The work is described as "the back end of the production pipe." This is not a pathway to IP ownership; it's a permanent service position.

Korea captured full value chain control. CJ Entertainment doesn't just produce content—it finances, distributes, exhibits through its multiplex chain, and licenses globally. K-pop agencies don't just manage artists—they own the IP, develop merchandise, produce games, and extend into media ecosystems (Weverse, V LIVE) that capture fan spending.

China built domestic platforms and protected domestic markets while developing capabilities. Chinese consumers spend on Chinese games (Honour of Kings, Genshin Impact) distributed through Chinese platforms (WeChat, Douyin ecosystem), generating value captured by Chinese companies.

India's Orange Economy provides training for the execution layer while making no provision for moving up the value chain. By 2030, the 2 million AVGC professionals will have excellent technical skills. Most will use them to enhance other nations' creative assets, just as India's 3 million software developers maintain Microsoft, Oracle, and SAP platforms without creating competing Indian software ecosystems.

Metrics Without Investment, Training Without Capacity

India's challenge in the creative industries is not workforce capability. 260,000 AVGC professionals already contribute to Oscar-winning visual effects. The challenge is structural positioning within global creative value chains. Training more workers doesn't change that positioning; it deepens the dependency.

The comparison with Korea and China is stark. Korea invested approximately 265 times more per capita in cultural industries and explicitly funded the development of "globally competitive IP". China spent decades supporting the transition from service work to IP ownership, producing companies like miHoYo (valued at $23 billion) that capture global franchise revenue. India's Rs 250 crore AVGC allocation trains workers to join the execution layer.

The fundamental question the Orange Economy fails to answer: once India trains 2 million AVGC professionals, who will own the content they create? If the answer is "whoever commissions the work from Indian studios"—as it is today, with 70% of VFX revenue from outsourced international work—then India will have succeeded at employment generation while failing at wealth creation.

Korea didn't become an entertainment superpower by training K-pop trainees; it became one by building SM Entertainment, HYBE, and CJ Entertainment—companies that own the artists, content, and distribution. China didn't build a $50 billion gaming industry by training coders; it built miHoYo, Tencent, and NetEase—companies that own Genshin Impact, Honor of Kings, and Identity V.

India's Orange Economy, as currently structured, will produce skilled workers and generate impressive training statistics. Whether it will produce an Indian Pixar, CJ Entertainment, or miHoYo depends entirely on investments the budget does not make. Meanwhile, the saffron economy continues: Adani expands airport operations, Ambani consolidates telecom and retail, electoral bonds channel corporate money to political parties, and public resources flow to private oligarchs who build airports and malls rather than animation studios or game development companies.

The orange branding is aspirational messaging. The saffron reality is extraction. India's creative professionals will continue to deliver world-class execution on other people's intellectual property.

Further Reading

Korea Herald: W7.85 Trillion Budget for 2026 Cultural Sector

International Trade Administration: South Korea Entertainment & Media

Hollywood Reporter: Meet the Most Important Mogul in South Korean Entertainment

Caixin Global: Ne Zha 2 Heralds New Era for Chinese Animation

Xinhua: Strong Year for Animation Propels China's Film Industry

Game Rant: Genshin Impact Creator miHoYo Reaches $23 Billion Valuation

Pranab Bardhan: Unmasking India's Crony Capitalist Oligarchy

TIME: What Adani's Downfall Says About India's Crony Capitalism

FasterCapital: Brand Licensing in Entertainment - Hollywood's Hidden Revenue Stream

Write a comment ...