On the day Parliament passed a bill named "peace," I thought of my father—who spent his life fighting for disarmament and died before the full weight of India's nuclear ambitions could crush the communities he sought to protect.

My father, J Sri Raman, founded Journalists Against Nuclear Weapons in 1998, days after Vajpayee's government conducted the Pokhran-II tests. It was an audacious act of protest at a moment when mainstream Indian media was celebrating the bomb. He went on to co-found the Movement Against Nuclear Weapons and the Coalition for Nuclear Disarmament and Peace, writing for Truthout and the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, warning anyone who would listen about the catastrophic logic of nuclear deterrence.

He died in November 2011—two months after fifteen thousand people began gathering daily at a church in Idinthakarai, Tamil Nadu, demanding that the Koodankulam nuclear plant not be commissioned. He had just written about Fukushima. He never wrote about Koodankulam. I have wondered, in the fourteen years since, what he would have said.

On December 17, 2025, I received a partial answer. The Lok Sabha passed the SHANTI Bill—the Safe and Harnessed Atomic Nuclear Technology for India Bill—by voice vote after the Opposition walked out. The bill opens India's nuclear sector to private corporations, caps liability at levels unchanged since 2010, and most consequentially, eliminates the provision that allowed plant operators to seek recourse against suppliers for defective equipment. A bill named "peace" granted immunity to the very corporations whose faulty components could cause the next Bhopal.

I believe my father would have found the name unbearable.

The Grammar of Peaceful Destruction

India's nuclear establishment has always spoken the language of peace while preparing for annihilation. This is not a metaphor; it is documented history.

On May 18, 1974—Buddha Jayanti, the anniversary of the Buddha's birth—India detonated its first nuclear device in the Rajasthan desert. The official designation was "Peaceful Nuclear Explosion." The code name was "Smiling Buddha." For two decades, the government maintained the fiction that India had merely conducted a civilian experiment in moving earth for mining and canal construction.

Raja Ramanna, the physicist who led the program, eventually admitted what everyone knew: "The Pokhran test was a bomb, I can tell you now... An explosion is an explosion, a gun is a gun, whether you shoot at someone or shoot at the ground."

The peaceful explosion used plutonium from a reactor Canada had provided for civilian purposes. The line between atoms for peace and atoms for war was erased at the moment of India's nuclear birth—and the erasure was deliberate. As M.V. Ramana has documented, the same scientists who built India's civilian reactors built its bombs. The same institution—the Department of Atomic Energy—promotes nuclear power and develops nuclear weapons. The regulator, the Atomic Energy Regulatory Board, reports to the very department it ostensibly oversees.

This institutional architecture was not an accident. It was designed to allow nuclear expansion to proceed without democratic interference, wrapped always in the language of development and peace.

The Bomb and the Bigot

My father understood something that many liberal commentators preferred to ignore: India's nuclear program was never simply about security. It was about Hindu nationalism.

The Bharatiya Jana Sangh—the BJP's predecessor—first called for a nuclear India in the 1950s. M.S. Golwalkar, the RSS ideologue whose writings still circulate in shakhas across the country, interpreted the Bhagavad Gita as a religious mandate for nuclear weapons—the cosmic duty of Hindus to take up atomic arms.

When Vajpayee's government conducted Pokhran-II in May 1998, Operation Shakti—"divine power"—the religious subtext became text. The Vishwa Hindu Parishad campaigned to build a temple to the goddess Shakti at the test site. May 11 was declared National Technology Day. The bomb was the culmination of Hindutva's long project of masculine assertion through technological violence.

My father wrote about this connection in 2001, addressing the World Conference against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs: the 1998 tests were "a big bang for majoritarian bigotry." He rejected the comfortable liberal distinction between India's supposedly defensive nuclear posture and the aggressive nationalism that animated it. The bomb and the bigot were inseparable.

Abdul Kalam's elevation—from missile program director to President—served a specific ideological function. A Muslim face on Hindu nationalism's most cherished achievement allowed the BJP to project inclusivity while advancing its core project. Kalam was not a departure from nuclear nationalism; he was its most effective public relations.

I say this as someone who grew up in a household where Kalam was not celebrated. My father taught us to see through the hagiography to the missiles beneath.

Koodankulam: The Women Who Carried Peace on Their Shoulders

The Koodankulam nuclear plant was agreed upon in 1988, when Rajiv Gandhi signed a memorandum with Mikhail Gorbachev—two years after Chernobyl, seven months after Gandhi himself had delivered the most comprehensive government disarmament proposal in history to the United Nations. The contradictions of Congress's nuclear policy are old and deep. But the resistance to those contradictions is equally old.

When Fukushima melted down in March 2011, the fishing communities around Koodankulam understood immediately what the DAE's reassurances were worth. They had been promised safety for two decades. Now they watched a technologically advanced nation prove that nuclear accidents remained possible, and that when they occurred, the consequences lasted generations.

In September 2011, the People's Movement Against Nuclear Energy began a sustained protest. For eleven consecutive days, between fifteen and twenty-five thousand people gathered daily. Over one hundred thousand participated across the months that followed. They held candlelight vigils, conducted hunger strikes, and stood in the ocean in "jal satyagraha"—a Gandhian assertion of their right to the sea that sustained them.

What distinguished Koodankulam from other Indian protest movements was the centrality of women. S.P. Udayakumar, who led the movement and now faces over three hundred criminal cases, has said plainly: "The women made all the difference... They carried the struggle on their shoulders."

I want to name some of these women, because the SHANTI Bill is designed to make them invisible.

Xavier Amal, known as Xavier Amma, is a fifty-five-year-old single mother who sold idlis for five hundred rupees a day. She spent over 80 days in Tiruchirapalli Central Prison on sedition charges for participating in a peaceful protest. When she was arrested, the police strip-searched her. "They treated us like murderers or robbers," she told researchers. She now faces charges of sedition and waging war against the state—for demanding that her community not be irradiated.

Sundari, a fish worker's wife, has 350 cases against her, including 24 sedition charges. Her testimony cuts to the gendered core of nuclear resistance: "When a man fights and goes to jail, it is different. When a woman goes, she is separated from her children, and when she gets out of jail, her family disowns her. They are ashamed of her." Her extended family stopped speaking to her after her release. Yet she continues: "The more cases they put, the more focused I am in the struggle."

Melret Raj began protesting at sixteen, when her mother took her to a rally against Rajiv Gandhi's laying of the foundation stone in 1988. Now in her forties, she describes the movement's rhythm: "We didn't sleep for those years. We would go to the church after feeding our families, sit there until evening, come home, cook again, and go back and sleep there."

Nearly nine thousand people from Idinthakarai—essentially the entire village—were charged with sedition. The state's response to peaceful protest was to criminalise a community. When Prime Minister Manmohan Singh blamed "foreign NGOs, mostly based in the US" for the protests, he was not merely deflecting; he was laying the groundwork for the repression that followed.

On September 10, 2012, police fired on protesters during uranium fuel loading. Anthony John, a forty-eight-year-old fisherman, was killed at Manappadu. He is not a name that appears in discussions of the SHANTI Bill. He should be.

The Economics of Socialised Risk

I am a development economist. I have spent my career evaluating programs, measuring outcomes, and assessing whether interventions deliver on their promises. Let me apply that lens to India's nuclear ambitions.

The SHANTI Bill promises 100 gigawatts of nuclear capacity by 2047—India's centenary. This would require approximately fifteen lakh crore rupees in investment. The government frames this as essential for "Viksit Bharat" and net-zero by 2070.

Here is what the economics actually shows:

Cost overruns are not exceptions; they are the pattern. Koodankulam Units 1 and 2 were projected to cost ₹13,171 crore and take five to seven years. They cost ₹22,462 crore—a seventy per cent overrun—and took over eleven years. Units 3 and 4 have already doubled their projected cost to ₹39,849 crore before completion. In 2004, the DAE projected 20,000 megawatts of nuclear capacity by 2020. India achieved 8,180 megawatts—a fifty-nine per cent shortfall. After sixty years of investment, nuclear power contributes three per cent of India's electricity.

Renewables have overtaken nuclear economically. Solar PV now costs approximately $0.038 per kilowatt-hour; wind ranges from $0.025 to $0.070. India's record solar auction achieved $0.015 per kilowatt-hour. Nuclear power, globally, costs $0.075 to $0.110, three to seven times more than other energy sources. In fiscal year 2024-25, India added 29.52 gigawatts of renewable capacity—more than the entire nuclear base of 8.88 gigawatts over its sixty-year history. Solar and wind projects move from approval to operation in one to three years; nuclear takes ten to fifteen.

The risk distribution is regressive by design. The SHANTI Bill caps operator liability at ₹3,000 crore per incident. Anything beyond is covered by a government-managed Nuclear Liability Fund, funded by taxpayers. For context: the Fukushima cleanup has already exceeded $182 billion, as Shashi Tharoor noted in Parliament. Bhopal's settlement, inadequate as it was, exceeded the SHANTI Bill's liability cap.

Private corporations under SHANTI will provide land, cooling water, and capital. The state-owned NPCIL will operate the plants and bear the liability. If a catastrophe occurs, the liability cap kicks in. Beyond that, the public pays. Profits are privatised; catastrophic risk is socialised. This is not development economics; it is extraction economics.

The fifteen lakh crore rupees required for 100 gigawatts of nuclear could alternatively fund approximately 300 gigawatts of solar, comprehensive grid storage, and distributed energy access for millions of households that currently lack reliable electricity. The opportunity cost is not abstract. It is villages without power, hospitals without backup, and schools without fans in May.

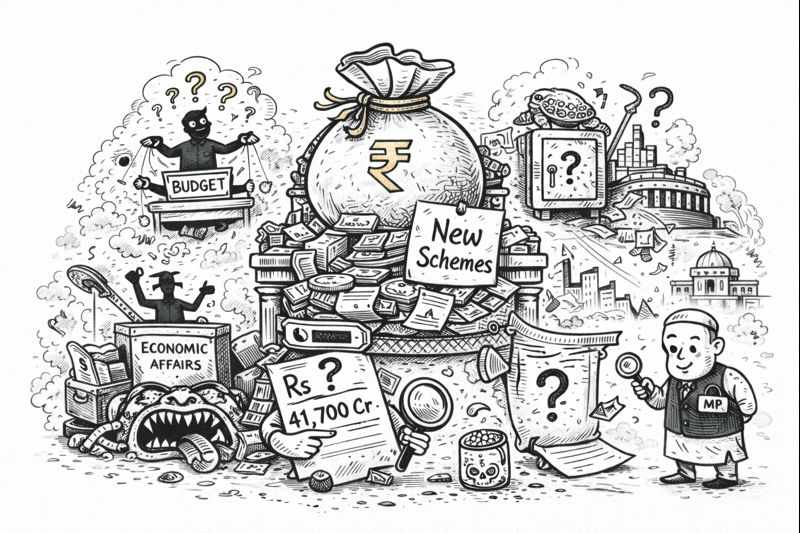

The Corporate Constellation

Let me name the beneficiaries, because the SHANTI Bill debate has been curiously reluctant to do so.

Adani Group's CFO Jugeshinder Singh stated the company was "deeply interested" in nuclear but was awaiting "clear liability laws... essential for efficient execution of nuclear projects." The SHANTI Bill provides exactly that. Gautam Adani personally visited the Tarapur Atomic Power Station in February 2025. In Parliament, Manish Tewari noted that Adani's nuclear announcement came weeks before the bill's introduction: "Is this a coincidence?"

Reliance Industries is in active discussions for approximately ₹44,000 crore in nuclear investment. The electoral bonds data reveal that Qwik Supply Chain Pvt Ltd—linked to Reliance through shared directors at Dhirubhai Ambani Knowledge City—was the third-largest electoral bond purchaser, with the overwhelming majority of bonds going to the BJP.

Vedanta issued a global invitation in February 2025 to partner on building 5,000 megawatts of captive nuclear capacity. An energy-intensive mining conglomerate wants to internalise baseload power while the public bears accident risk.

Larsen & Toubro already holds multi-billion rupee construction contracts at Koodankulam Units 3-6. Under the 2010 liability law, they faced potential recourse claims if their equipment proved defective. Under SHANTI, that exposure disappears.

The international beneficiaries are equally clear. Westinghouse, GE-Hitachi, and EDF refused to enter India precisely because Section 17(b) of the Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act allowed operators to seek recourse against suppliers. Russia's Rosatom received contractual immunity under a 2008 agreement and has been India's reliable nuclear partner ever since. The SHANTI Bill extends to Western suppliers what Russia already enjoyed.

The liability law that deterred them was shaped by the Bhopal disaster. Survivors of that disaster—who are still fighting for adequate compensation four decades later—demanded that suppliers not escape accountability for defective equipment. Their demands were partially incorporated into the 2010 law. The SHANTI Bill erases that victory.

The Triple Irony of SHANTI

The name demands one final accounting.

In 1974, India called a nuclear bomb a "Peaceful Nuclear Explosion." In 2011-2012, people demanding peace—demanding that their communities not be irradiated—were charged with sedition and "waging war against the state." In 2025, a bill called "SHANTI" removes protections for communities and shields the corporations whose equipment could irradiate them.

Peace, in India's nuclear grammar, has always meant peace for the nuclear establishment. Shashi Tharoor's warning in Parliament was precisely calibrated: "Let us ensure that this name is not a cruel irony in the aftermath of a preventable disaster."

But the cruelty is not prospective. It is already here. It is Xavier Amma who was strip-searched in custody. It is Sundari who her family disowned. It is Anthony John who was shot dead at Manappadu. It is nine thousand villagers charged with sedition for asking not to be poisoned.

The SHANTI Bill does not promise peace. It promises impunity—for suppliers, for corporations, for the nuclear establishment that has operated without democratic accountability since Homi Bhabha convinced Nehru that atoms could make India modern.

My father spent his life fighting for a world without nuclear weapons. I am fighting for a world where the communities in the shadow of nuclear plants are not treated as expendable. These are not separate struggles. They are the same struggle, viewed from different distances from the blast radius.

Conclusion: What Peace Requires

My father wrote in 2001 that the 1998 tests were not about security but about "majoritarian bigotry." He understood that nuclear weapons were continuous with the broader project of Hindu nationalist assertion—that the bomb was not separate from the pogrom.

I am arguing that nuclear energy in India is continuous with the same political economy. The communities being irradiated are Adivasi, Dalit, fishing-caste, and Muslim. The corporations being enriched are the same corporations that fund the BJP through electoral bonds. The regulatory capture is the same capture that allows environmental clearances for projects that destroy livelihoods.

The SHANTI Bill is not about energy security. India's energy future lies in solar and wind, in distributed generation, and in technologies that do not require evacuating a thirty-kilometre radius when they fail. The bill is about something else: about ensuring that when the next Fukushima occurs in India—and the DAE's safety record suggests it will—the Adanis and Reliances and Westinghouses will be protected, and the fisherwomen of the next Idinthakarai will not.

My father died before he could write about Koodankulam. The Coalition for Nuclear Disarmament and Peace, which he co-founded, took up that struggle after his death. I am taking it up now, fourteen years later, with the tools he gave me: the capacity to see through official language to the violence it conceals, the refusal to accept that some communities are disposable, the insistence that peace means something more than impunity for the powerful.

The SHANTI Bill is not peace. It is the grammar of peaceful destruction, extended from bombs to reactors, from Pokhran to Koodankulam to whatever community will next be told that their sacrifice is necessary for national development.

I reject that grammar. I reject it in my father's name, and in the names of the women who carried Koodankulam on their shoulders, and in the name of every child in Jaduguda whose cells are dividing wrong because uranium tailings were used to pave their roads.

Peace requires accountability. Peace requires communities to have the power to refuse. Peace requires that when corporations provide defective equipment, they cannot hide behind liability caps and government indemnification.

The SHANTI Bill offers none of this. It offers only the peace of the irradiated—the silence that follows when dissent has been criminalised and the exposed have been compensated at rates that assume their lives were worth less than the electricity generated from their suffering.

That is not peace. That is conquest by other means. And I will not call it by any other name.

The author is a development economist and the daughter of J Sri Raman (1943-2011), journalist and founder of Journalists Against Nuclear Weapons.

Notes

On my father's position on nuclear energy: I must be honest about something. My father, while staunchly demanding an end to nuclear weapons, had not argued for a rejection of nuclear energy. This is documented in the obituary published by CPI(ML) Liberation after his death: "Now that the debate on nuclear energy in India and the world has emerged with a new urgency post-Fukushima, we will miss Sri Raman's insight in approaching the question anew." I do not know what position he would have taken. The Fukushima disaster occurred eight months before he died. Koodankulam escalated two months before. His last articles engaged with the liability law, invoking Bhopal as a reason for supplier accountability—the very accountability the SHANTI Bill now eliminates. But I know what I have concluded, and I believe my conclusions are consistent with his life's work, even if they extend it.

The distinction between nuclear weapons and nuclear energy is institutionally meaningless in India. The same department develops both. The same scientists have worked on both. The same nationalist ideology drives both. The plutonium for Smiling Buddha came from a civilian reactor. My father founded organisations to oppose nuclear weapons because he understood that the logic of deterrence was the logic of civilisational suicide. I oppose nuclear energy in India because I understand that the logic of liability caps is the logic of disposable communities.

On Congress and contradictions: I remain a supporter of Congress. This requires explanation, given what I have written. Congress's nuclear history is a history of contradictions. Nehru cultivated deliberate ambiguity. Indira Gandhi conducted Pokhran-I despite objections from her principal secretary, D.P. Dhar, who feared economic sanctions. Rajiv Gandhi signed the Koodankulam agreement while simultaneously proposing global disarmament. Manmohan Singh pushed through the Indo-US nuclear deal over Left opposition. But Congress is a party of plurals. The dissenting tradition exists. Dhar and P.N. Haksar opposed Pokhran-I at the highest levels. Shashi Tharoor's parliamentary opposition to SHANTI was substantive and documented. Manish Tewari raised the question of the corporate beneficiarydirectly. The party's restraint—however compromised by its own nuclear record—contrasts with the BJP's aggressive nuclear nationalism, with Golwalkar's cosmic mandate, with 11 May as National Technology Day. I do not ask Congress to be pure. I ask it to be what it has sometimes been: a space where anti-nuclear voices can exist, where the DAE's propaganda can be questioned, where Idinthakarai's women are not enemies of the state.

Write a comment ...